Being Borderline in Britain: A Women’s Issue

Recent data and conversations collected by Hybrid have revealed a female crisis that is often neglected and stigmatised by medical professionals.

Borderline Personality Disorder, commonly known as BPD is a complex mental health condition that is characterised by intense mood swings, a lack of sense of self and persistent suicidal and self-destructive behaviour.

BPD is a chronic condition and is lifelong, often caused by traumatic events in childhood, with a genetic component also playing a part in its development. Recent conversations surrounding the condition on platforms such as TikTok have led to many self-diagnosing with the disorder, with some questioning the validity of their diagnosis.

To dig deeper, Hybrid conducted a small-scale survey of BPD support groups in the UK to gather opinions as well as data, resulting in 18 random responses, we then compared this data to results from the 2014 Annual Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. (APMS)

The survey itself screened members of the general population for a variety of mental illnesses and gathered information such as gender, age, and other factors such as medication they take and benefit status. In respect to personality disorders, the survey screened for Borderline Personality Disorder as well as Antisocial Personality Disorder, also known as sociopathy.

Alongside this, we interviewed Maisie, 21, a student mental health nurse with BPD, to discuss her thoughts on how BPD is treated. This helped to understand what life can be like with the condition.

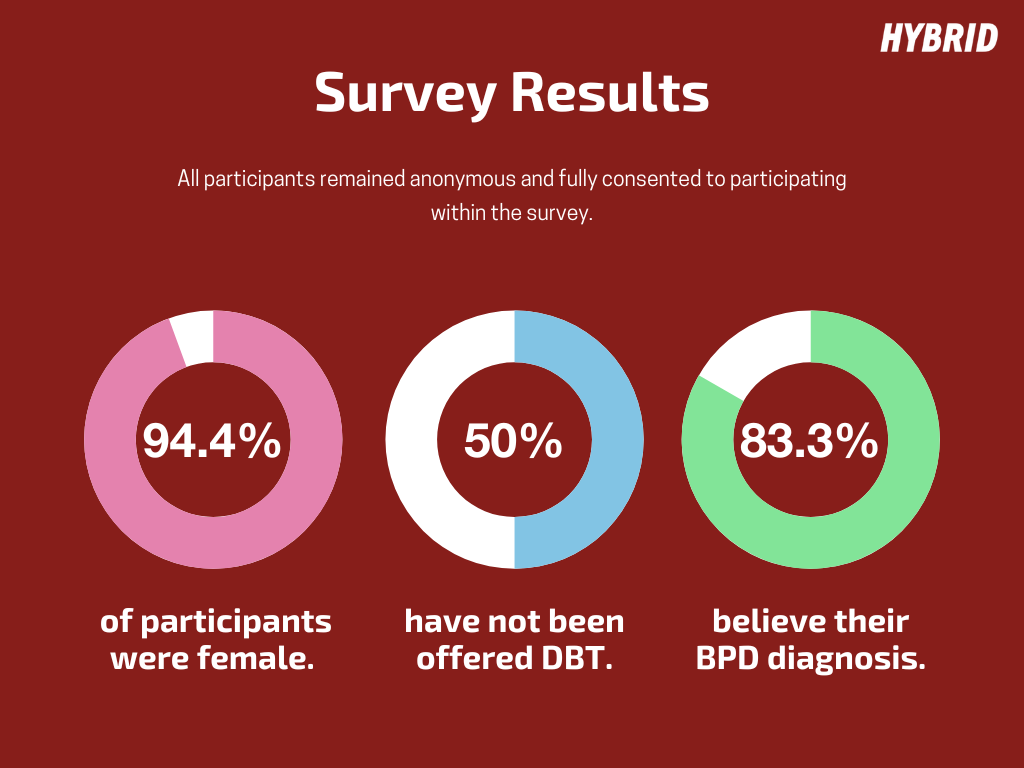

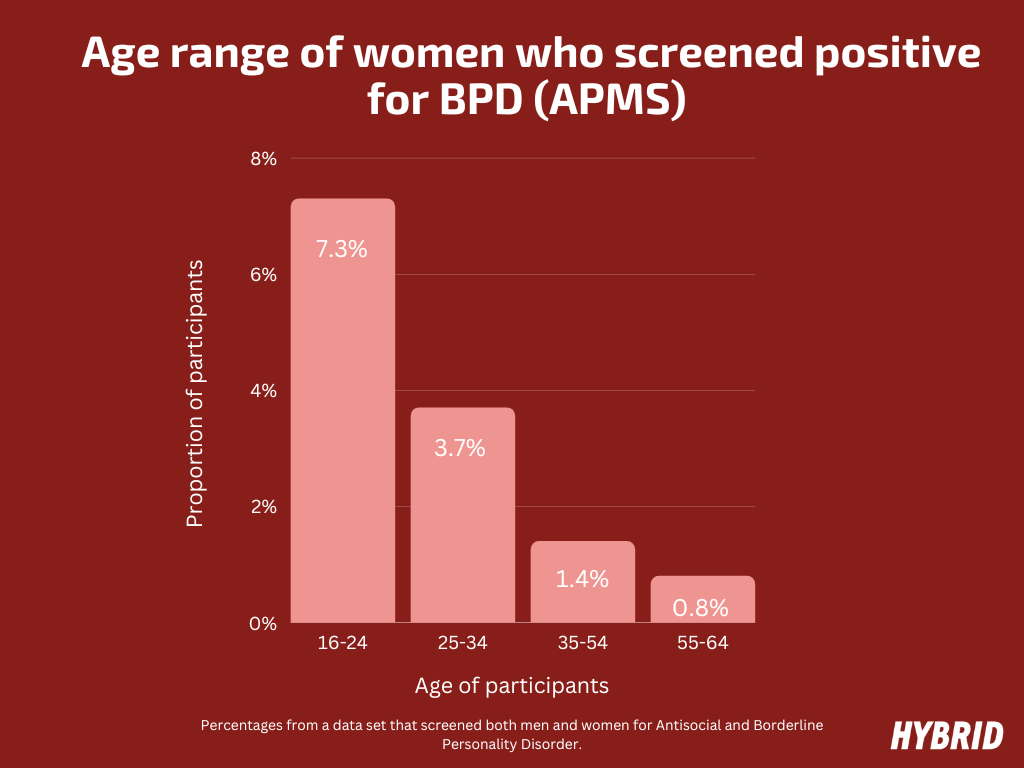

The results from our survey revealed that 94.4% of participants identified as female, reflecting the claim that women are overrepresented in terms of a BPD diagnosis. Furthermore, the most common age that participants were diagnosed was 18. This statistic was also reflected in the APMS, of the women screened for BPD, the most prevalent age range was within the 16-24 group with 7.3% screening positive (around 22 women).

For Maisie, the high number of female participants didn’t surprise her, as she believes that “the disorder is misdiagnosed very easily.” Her explanation behind the overrepresentation of females came down to the way in which the disorder presents itself.

“Females tend to show emotion a lot more and it’s generally more acceptable for females to talk about their mental health than males.” She argues that the disorder isn’t “caught enough in males as there is a higher rate of suicide within this demographic, so by the time it should be caught, it’s too late, they will have ended their life.”

There is also the issue of gender differences that can affect personality disorder diagnosis, ASPD is more likely to be diagnosed in males, whilst BPD is more likely to be diagnosed in females. The results of the APMS study showed these distinct patterns. Among the 3,068 women screened for ASPD (Antisocial Personality Disorder) and BPD (Borderline Personality Disorder), approximately 1.8% (around 55 women) were identified as having ASPD, while approximately 2.9% (around 88 women) were identified as having BPD. On the other hand, among the 2,012 men who underwent the same screening, approximately 4.9% (around 98 men) were found to have ASPD, and approximately 1.9% (around 38 men) were found to have BPD.

Equally as concerning was that 50% of those surveyed had never received dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) treatment - the gold standard for alleviating symptoms of this condition.

The APMS also expanded on this pattern: Compared to any other personality disorder, 16.6% of borderlines had requested but not received a particular mental health treatment in the past 12 months, this was over double that of other personality disorders, at 7.3%

This therapy can help to reduce symptoms and radically improve sufferers’ lives. Yet, waiting lists can often be lengthy for such a specialist therapy and this is often dangerous in a disorder that coincides with frequent suicide attempts.

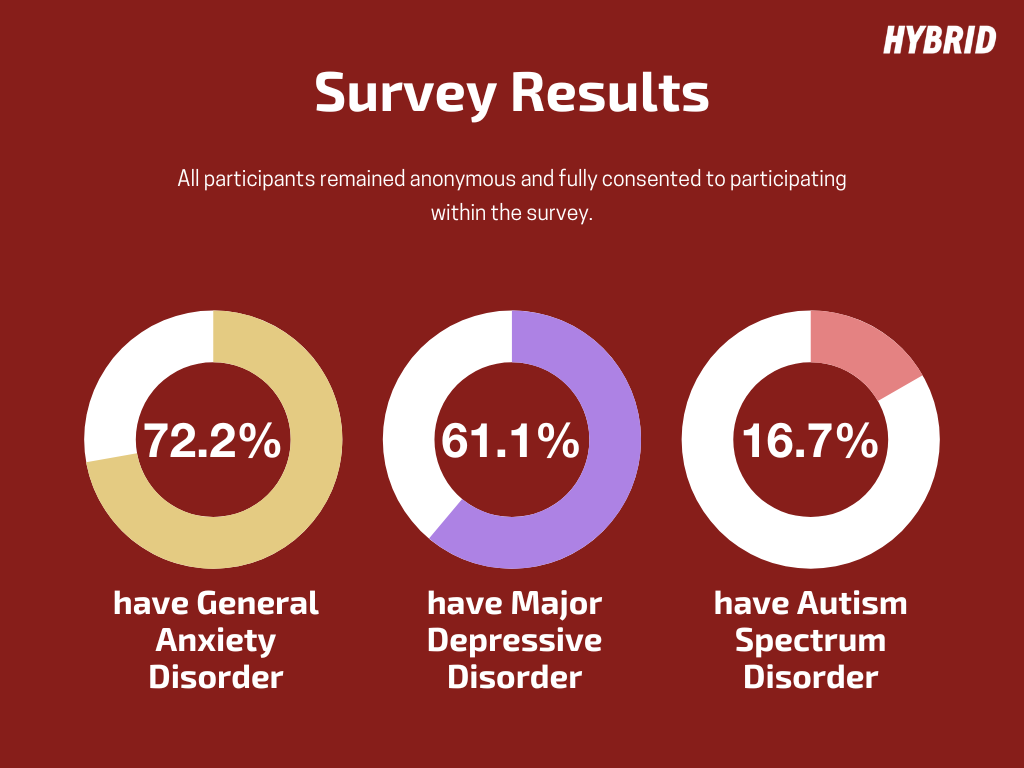

BPD often co-occurs with a multitude of conditions, with our survey showing that 72% suffer from General Anxiety Disorder, 61% have Major Depressive Disorder and 16.7% have Autism Spectrum Disorder. The APMS also illustrated this comorbidity with 36% taking medication for anxiety and 36.8% taking medication for depression.

With a high likelihood of co-occurring disorders, there is a chance for misdiagnosis. Maisie believes this happens “often with autism and BPD because the symptoms all cross over. Those with autism also struggle with emotional management and impulsivity and that plays a big part in BPD.”

This has been backed up by recent research into this phenomenon, which has led to “growing awareness that (Autism and BPD) share surface symptom similarities contributing to challenges in differential diagnostic assessment.”

Discussions of autistic women being misdiagnosed with BPD have blown up over TikTok in recent months, igniting a wider conversation about the way that women’s health is often neglected by medical professionals.

Some feel the label is too easily handed out, whilst others on the app self-diagnose, believing that they fit the diagnostic criteria. Maisie, as both nurse and patient, has been disheartened by the way she’s seen medical staff speak of those with BPD.

“If I’m brutally honest, I’ve seen a lot of negative attitudes. If a patient is in a crisis you get comments, palming them off in the office, claiming they are a big borderline. Maisie believes that repeated suicide attempts, a common part of BPD, mean that medical staff “don’t ever believe the person will end their life.”

As Maisie emphasises, this is a dangerous assumption, with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) claiming that up to “1 in 10 with the disorder will die by suicide.”

This has detrimental effects on a patient’s treatment too. “A lot of therapists I've looked into won’t take patients with BPD just because they have a belief that we are impossible to work with.”

This is a harmful stereotype, considering that BPD, albeit ever-present, is a treatable personality disorder where individuals can make great strides in developing boundaries, regulating their emotions and redirecting themselves from self-harm.

Yet, in comparison to conditions such as Major Depressive Disorder and General Anxiety Disorder, medical professionals can’t rely on the perhaps, overused solutions of CBT therapy and antidepressants.

Many individuals with this disorder have developed it due to deep-rooted trauma that needs to be addressed and simple quick fixes are simply not appropriate.

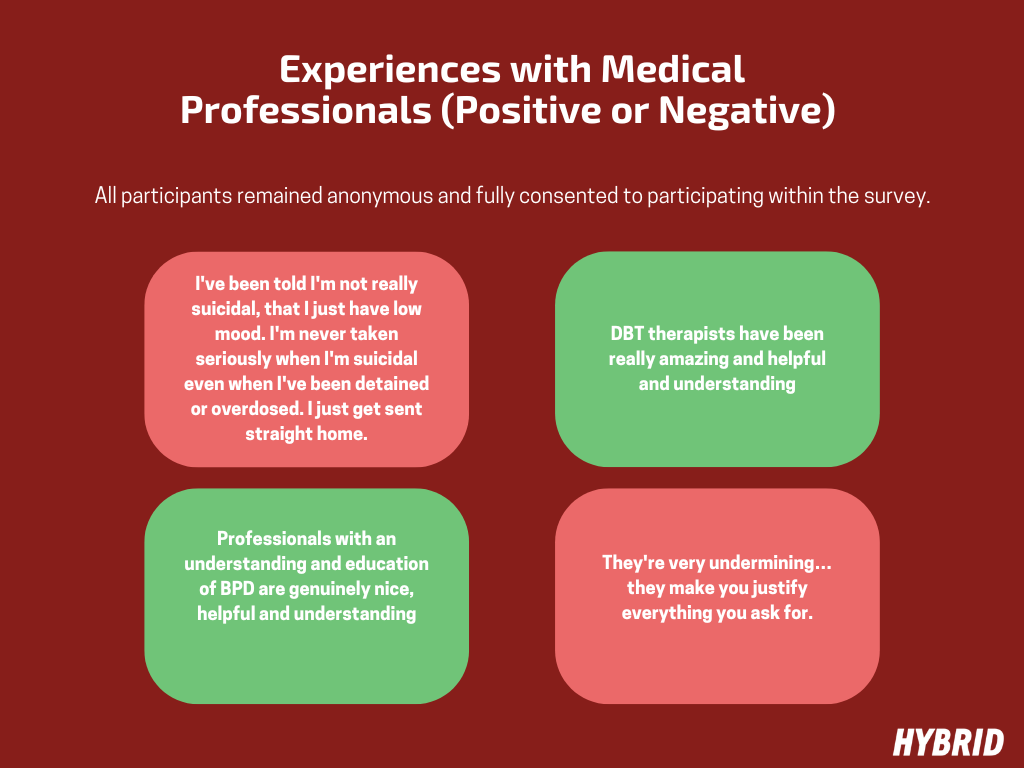

Anonymous individuals within our survey were given the opportunity to reveal their positive or negative experiences with treatment. Many reiterated the negatives that Maisie addressed, particularly stereotypes.

One of our participants felt they were labelled as an “attention seeker… I was just abandoned, with no information on BPD, medics say they knew nothing about it.”

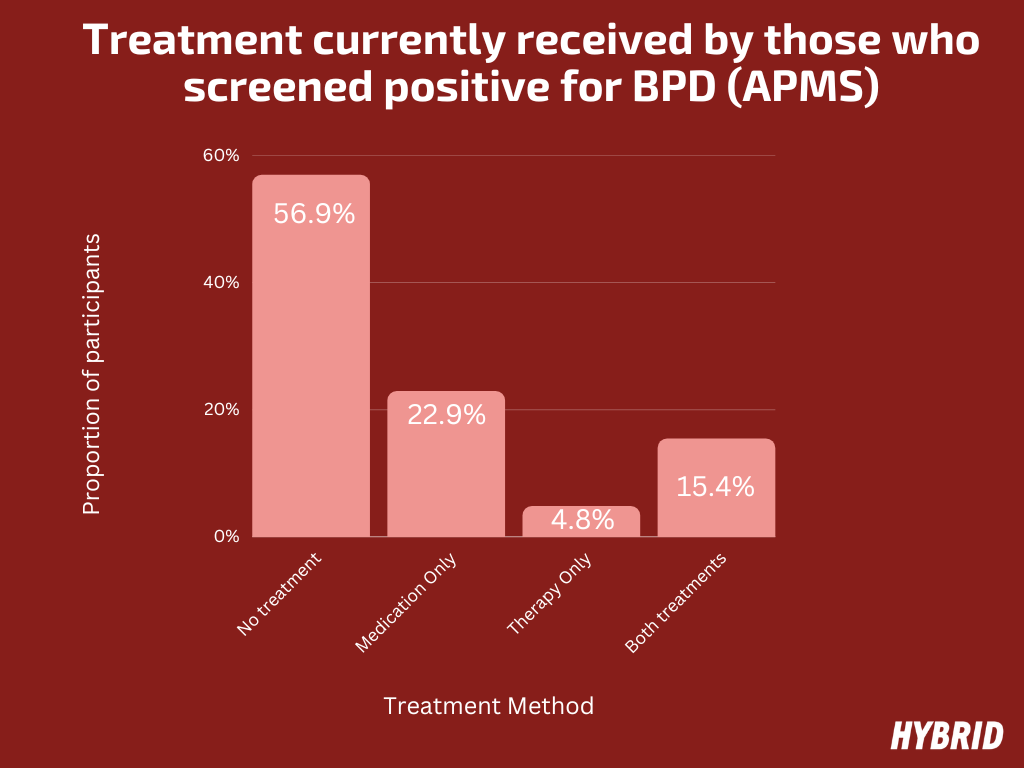

38.9 % felt like there was an over-reliance on medication but an equal proportion of participants felt there was a balanced mixture of medication and therapy. However, the APMS showcased that only 15.4% were receiving both counselling and medication and 56.9% were receiving no treatment at all.

The APMS showcased a lower reliance on medication in comparison with our figure, with a 70% reduction from 38.9% to 22.9%. However, this was still higher than those who relied on both medication and therapy, at 15.4%.

Those who discussed this over-reliance, felt like they were “palmed off with medication, that made me feel like a zombie.” Whereas some felt abandoned as they were left with “no medication for support and no support in-between diagnosis and awaiting DBT.”

Whilst individuals like Maisie argue that the disorder is easily misdiagnosed, some participants have had the opposite problem, having to fight for a diagnosis. One individual described how “they knew they had something going on since they were a kid, but it’s taken me until almost 30 to be diagnosed.”

Perhaps, as Maisie suggests, there are two opposing issues surrounding BPD diagnosis. Certain medical professionals are reluctant to give a diagnosis, whilst some diagnose it too easily, due to overlapping symptoms with other disorders.

Considering the stigma that BPD sufferers face, it is unsurprising that medical professionals may be reluctant to give a diagnosis.

Whilst this may help avoid mistreatment by psychiatric professionals, it is also a double-edged sword with some desperately needing a diagnosis to receive life-changing DBT therapy. This contradictory treatment that BPD sufferers face is a reflection of a greater women’s rights issue.

Arguably, women with the disorder are criticised for seeking a diagnosis, yet, when they are diagnosed, their concerns are often silenced and framed as a dramatic presentation of the disorder.

This ignorance has consequences on physical well-being too, with BPD being an easy scapegoat for health concerns. Maisie’s journey with her physical health has been a difficult one. Constant pain around her abdomen was brushed off by medical professionals. After visiting A&E due to her inability to stop vomiting, her symptoms were attributed to her BPD, by a doctor.

It was only after pushing for scans and tests that Maisie was able to figure out the root of her problems. It was revealed that Maisie was suffering from a serious liver condition, caused by previous overdoses. If Maisie hadn’t challenged the undermining opinions of medical professionals, a dangerous medical condition would have been left untreated.

Maisie’s story is one of many, but it doesn’t undermine the validity of a BPD diagnosis. This condition is important and a label can be essential to individuals achieving a sense of mental wellbeing. The crux of the issue is not the disorder, but the way that the label is misused by medical professionals.

A diagnosis and treatment for BPD are imperative. Not only can untreated BPD affect one’s relationships and quality of life but the APMS has showcased a tangible economic impact, especially in relation to gender. Women with BPD were significantly more likely to be on ESA than men. Around 18.8% of women (approximately 24 individuals) who screened positive for BPD claimed ESA, whereas only 4.5% of men (around 5 individuals) with BPD did so. This represents a significant 76% reduction in the number of men claiming ESA with BPD compared to women.

Decades of research have showcased the validity of Borderline Personality Disorder and it would be unfair to dispute the research that has led to the creation of this diagnosis. Yet, with some medical professionals either refusing to hand out a diagnosis or gaslighting individuals who are diagnosed; women’s concerns are being ignored.

It’s impossible to ignore the wider issue at play here and that is the chronic underfunding of public services within the UK. The NHS is, arguably, on its knees, with chronic underfunding and understaffing, resulting in justified, recent strike action.

With treatment for issues such as depression and anxiety being hard to attain, more complex conditions like BPD are placed on the back burner. Psychiatric wards are often understaffed and unequipped to deal with personality disorders.

Ultimately, nothing is going to change until BPD is perceived as the treatable condition that it is. Women’s concerns need to be validated and addressed, but until funding is allocated towards training and greater treatment for personality disorders, the label is continuously going to be misinterpreted and misused, as an excuse to cut costs.

Quick fixes are not a solution to Borderline Personality Disorder, and it is insulting to assume that a disorder that is often caused by deep-rooted trauma can be solved with 6 CBT therapy sessions or a prescription for an antidepressant.

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on freephone 116 123, or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. You can also text SHOUT to 85258 to receive emotional support via text from a SHOUT volunteer.