Does Possession Still Win You Games?

A look at how football is being played in the Premier League through data

Tiki-taka football grew out of Johan Cruyff’s idea of total football, and for years fans and pundits repeated the same belief: if you keep the ball, it is your game to lose. Possession became a tool for dominance, especially in the Premier League, where it was often linked to control and stability. For a long time, this was widely accepted as the correct way to play. In recent seasons, though, that has not always been the case. High-pressing sides, counter-attacking teams and clubs who specialise in set pieces have all shown that you do not need to dominate the ball to get results over a season.

Looking at ten years of Premier League data helps reveal what is really happening beneath the surface. This analysis draws on league-wide trends, Manchester City’s evolving style under Pep Guardiola and the growing influence of set-piece goals under managers like Mikel Arteta. Concepts such as false possession and threat in transition raise a simple question: in today’s Premier League, does keeping the ball still win you games?

That is a Lot of Data

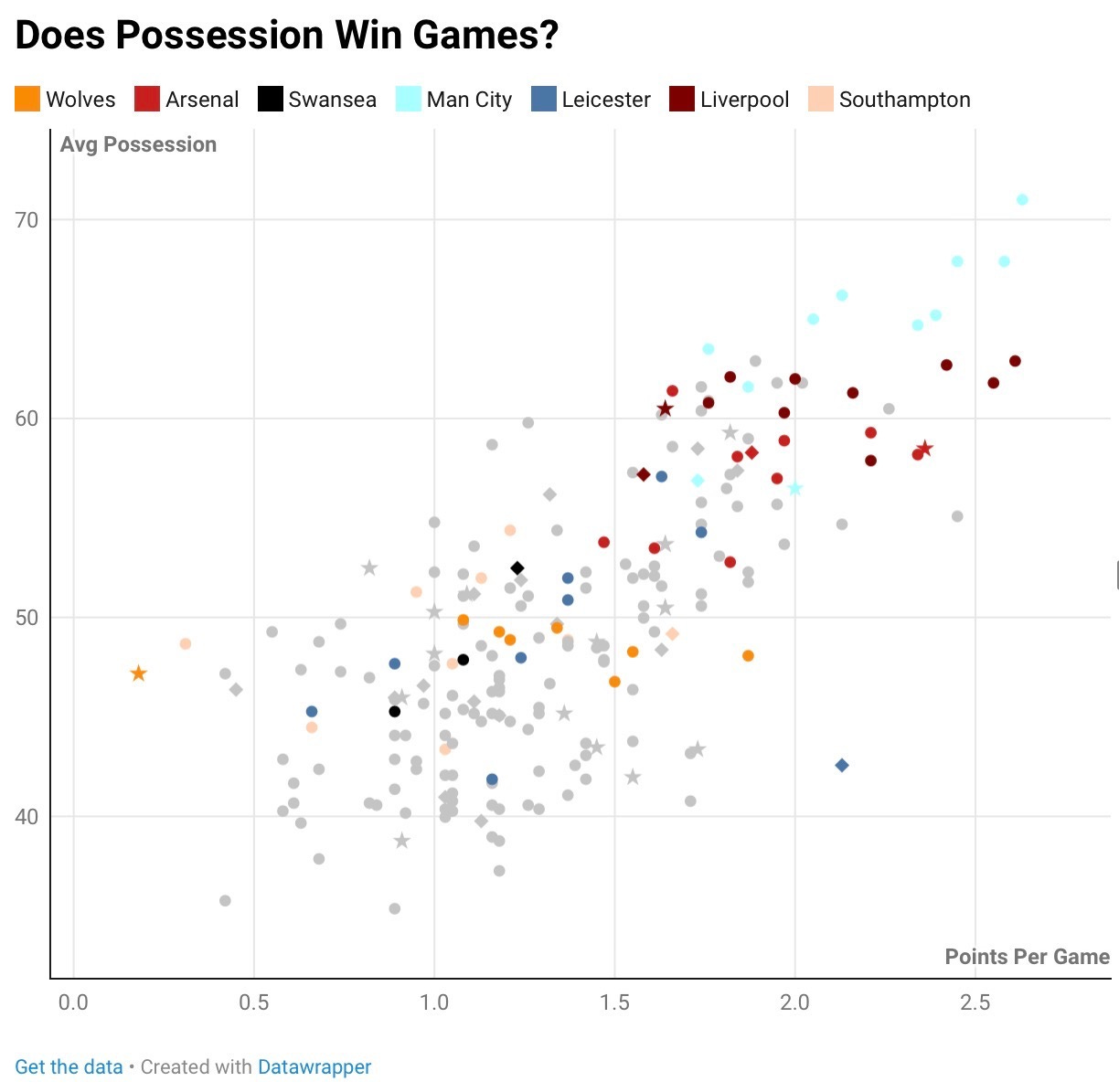

When you look across ten seasons of Premier League data, the relationship between possession and performance does not show the neat, upward trend people expect. The scatter graph makes this clear. Some teams with high average possession sit surprisingly low in points per game, while others who see far less of the ball finish much higher. It becomes obvious that possession alone does not explain who wins matches.

One reason for this is the idea of false possession. Some teams keep the ball for long periods but do very little with it. Late-era Swansea, Russell Martin’s Southampton, Wolves in their current shape and Kompany’s Burnley all posted strong possession numbers on paper, but much of that time came in harmless areas. They struggled to progress into the final third or create genuine threat. It looked like dominance, but it was not, and the league table reflected that.

Russell Martin’s Southampton were a huge talking point in the 2024/25 season. They often held the ball for large periods, but most of it was simply circulating without purpose. One Southampton fan summed it up bluntly: “It has its place, but as a tactic over 90 minutes it is stupid.” She also highlighted how badly the style matched the squad: “We would lose the ball at the back and concede easily. We did not have the players to execute the idea.” In the end, the possession became misleading. It created the illusion of control, but it did not turn into results.

Teams That Changed The System

There are also teams who do the exact opposite and outperform their possession because they are effective in the moments that matter. Leicester’s 2015/16 title season is the clearest example. They finished the year with only 42.6 per cent possession on average, yet won the league. Their compact defending, quick transitions and ruthless finishing allowed them to beat almost everyone they faced. It was not a statistical anomaly. It was simply a different way of playing.

More recently, Liverpool under Klopp and Aston Villa under Emery have shown how dangerous a team can be with far less of the ball. Their threat comes from transition moments rather than long spells of keeping it. They create high-quality chances straight after winning possession, before their opponents can reset. The scatter graph reflects this clearly. Several low-possession teams sit much higher in points per game than their possession numbers suggest they should.

These patterns help explain why the data does not fit the old possession narrative. Some teams keep the ball without threatening, while others threaten constantly without seeing much of it. Possession is no longer the reliable predictor many people assume it is. Modern Premier League football does not follow a single formula, and success comes in different shapes.

The Guardiola Way

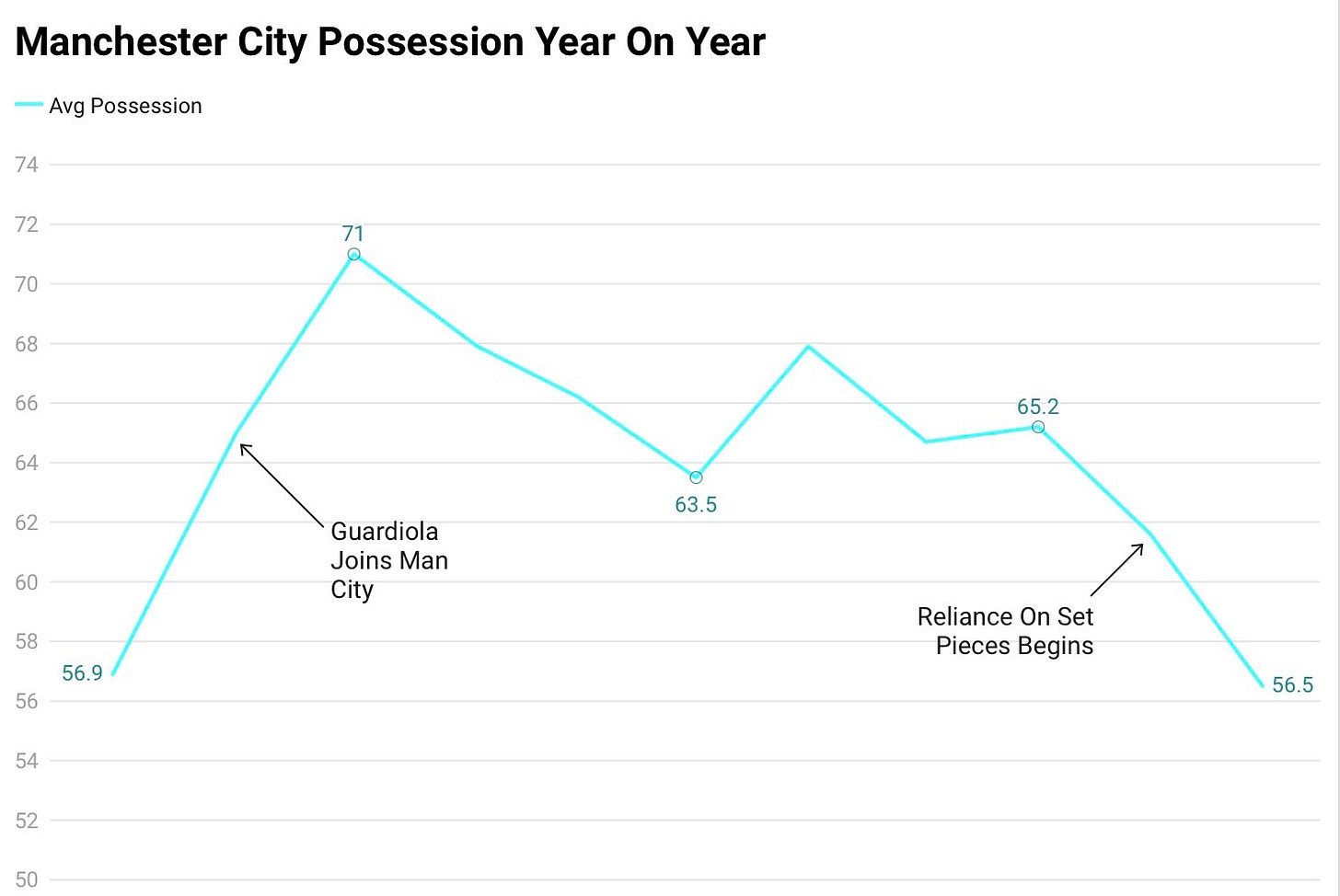

Manchester City are the most important team to look at when trying to understand how possession has evolved. Pep Guardiola built his reputation on possession football at Barcelona and Bayern Munich. Since arriving in the 2016/17 season, City have been held up as the example of what possession football is supposed to look like. However, their year-on-year numbers show a more interesting story.

City’s average possession peaked early in Guardiola’s tenure at 71 per cent, as shown by the line graph. In later seasons it stayed consistently over the 60 percent margin.

City were often criticised, with fans of the league noting that they “were removing flair” from the game. Jack Grealish is a notable example where supporters complained became “more conservative” in the way he attacked once leaving Aston Villa.

This season there has been a noticeable shift to 56.5 per cent in the most recent season. Despite these dips, City continued to win titles and control matches. This shift tells its own story.

City no longer need overwhelming possession to dictate games. Their control comes from structure, pressing, positioning and their ability to stop counters before they start. It is still a possession-based style, but it is no longer driven by the numbers themselves. Guardiola uses the ball to manage risk and manipulate space rather than to dominate purely through volume.

There are several reasons behind this change. The arrival of Erling Haaland encouraged quicker, more direct patterns of play, simply because he is one of the most lethal finishers the league has ever seen. Creative midfielders of the past such as: David Silva and Kevin De Bruyne have moved on. Even Guardiola’s preference in goalkeepers has shifted. For most of his time at City he prioritised keepers who were comfortable with the ball at their feet, like Ederson. This season he has preferred shot-stoppers such as Donnarumma and James Trafford, which suggests a different approach to control.

If even the club most associated with possession has changed the way it approaches dominance, it is not surprising that possession no longer predicts success across the league. City show that control depends on what a team does in the spaces around possession, not on how long they keep the ball for.

New Ways to Win

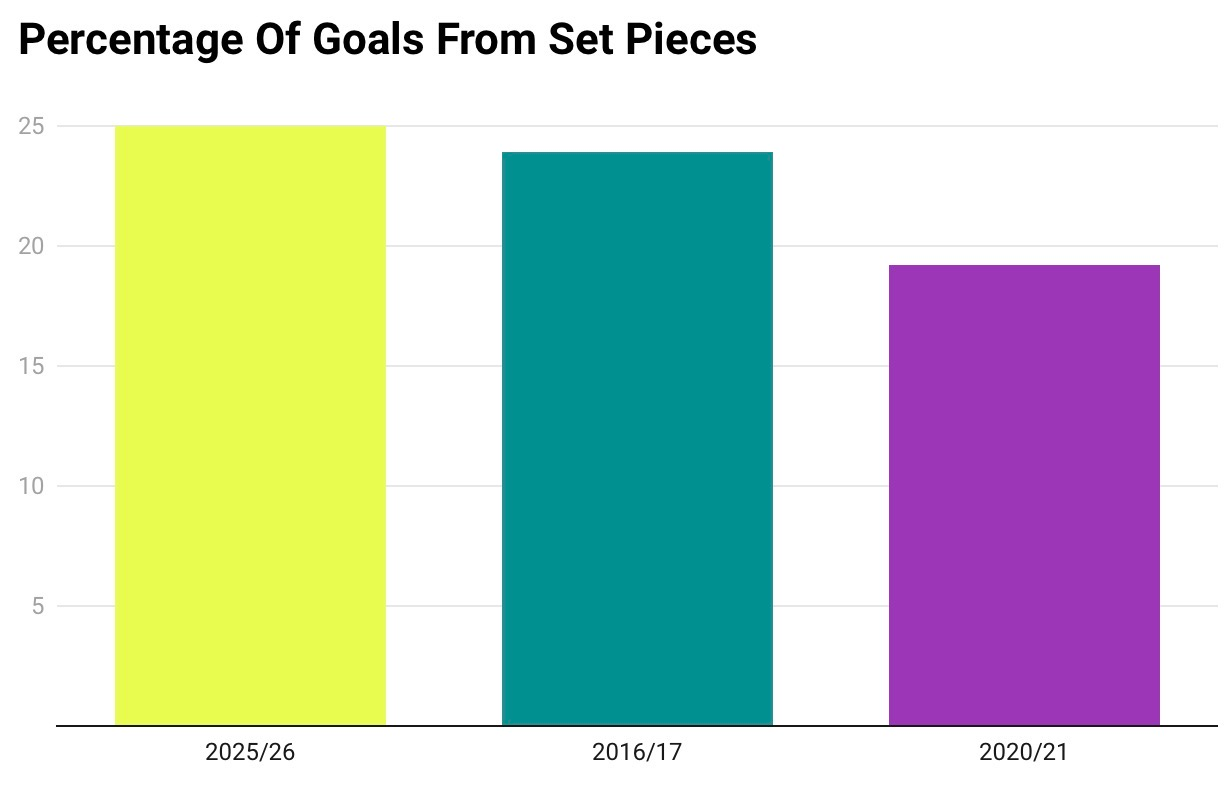

*excluding penalties

Possession also carries less weight now because set pieces have become one of the most reliable ways to score. The pie chart shows a clear increase in the share of goals coming from set pieces: numbers dipped in the 2020/21 season to just 19.2 per cent after which was right in the middle of Guardiola’s dominant reign. This year it sits at 25 per cent which is the highest in the last decade. This reflects the spike in set-piece coaching and analytics across the league.

Brentford have built a reputation on rehearsed routines, especially from throw-ins. Arsenal under Mikel Arteta have taken it even further. In 2025 they have become one of the most dangerous set-piece sides in Europe, scoring from corners and wide free-kicks with remarkable consistency. What makes this significant is that Arsenal still keep plenty of the ball. They simply see set pieces as an efficient route to goals.

Brentford use dead balls because they know they will not dominate possession. Arsenal use them to add an extra threat on top of their open-play control. Even the Southampton fan I interviewed noticed this shift, saying, “The way the game is structured around set pieces kills the game.” Whether or not you agree with that sentiment, it reflects a reality. Teams do not need long spells of possession to create their best chances. This is not necessarily a new phenomenon. Looking back there have been clubs like Stoke, Burnley and West Ham that have seen success playing defensively focused football.

Set pieces bypass possession almost completely. They allow teams with less of the ball to generate high-value chances, and in today’s Premier League these moments can be just as important as anything that happens in open play.

So Does Having More Of The Ball Win Games?

In the end, the data points in the same direction as the football itself. Possession still matters, but it does not decide matches on its own. Control now comes from structure, transitions and set-piece quality as much as time on the ball. The Premier League has evolved. Keeping the ball can still help you win, but it is no longer the thing that decides games.