“Even faculty feel frightened” says Oxford professor on the rise of ‘cancel culture’ on British university campuses

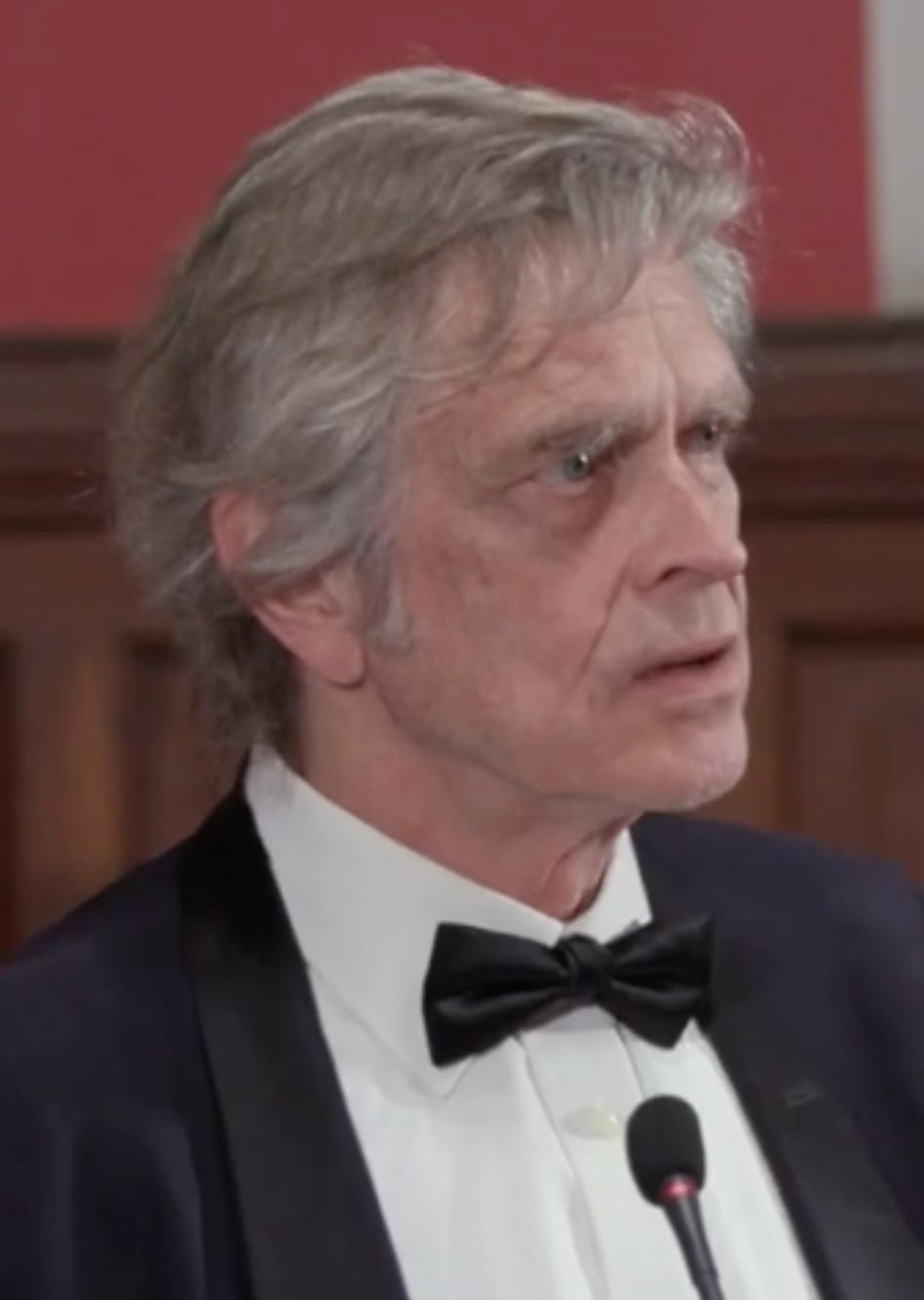

Professor of Moral Philosophy at Oxford, Jeff McMahan, warns of the “major threat” that is ‘cancel culture.’

Standing inside the porters’ lodge of Corpus Christi College, Oxford – founded in 1517 – looking across the quad, you can feel the history. You are reminded of the huge responsibility that such institutions have in shaping the rhetoric of the future. No better place, then, to discuss a topic such as ‘cancel culture’.

Looking at the time, I walked back out onto the street to see if my interviewee was, perhaps, waiting outside. Suddenly, looking to my right, down Merton Street, I see a man on a bicycle approaching at high speed; was he going to stop, I thought, or was he just going to take me out? Enter the purpose of my visit to Corpus: the emeritus fellow, Professor Jeff McMahan, moral philosopher.

“I think cancel culture is a curious and inappropriate term” says the American academic. We’re now sitting on some rather low, but quite comfy, sofas in the far corner of the College Senior Common Room, coffees in hand. “The term derives from this original use of the term of cancelling a speaker. That term spread.”

In October, this term is something the former Conservative Home Secretary, Suella Braverman, saw firsthand. She had to cancel her planned speech to her former college at Cambridge University after safety concerns were raised to her about the visit. This was because Pro-Palestinian supporters planned to target the event due to Braverman’s stance on Isreal-Gaza and called to “no platform” what they labelled as the “far right.” No platforming an individual links to Professor McMahan’s definition of ‘cancelling’ a speaker, giving them no platform to express their views.

Professor McMahan explains: “If someone is coming to the campus whose views you think are immoral, the thing to do is go to the event and refute the views publicly and put the person on the spot.”

The professor, now leaning forward to emphasise his point: “If you’re so confident that the person’s views are immoral, go and show why. If you can’t do that, then you shouldn’t be shouting the person down.”

The phenomenon of students ‘cancelling’ individuals has been in the headlines a lot recently. This is after some of Britain’s most notable authors, like Stephen Fry and Tom Holland, wrote to the Education Secretary, Bridget Phillipson. They accused the government of failing to uphold “humane and liberal values” on British university campuses.

Also, in Oxford, there was the recent tragic case of Alexander Rogers, the 20-year-old Corpus Christi student who sadly took his own life after being “ostracised” by peers following a sexual encounter where a woman expressed discomfort. An Independent Serious Incident Review commissioned by Corpus Christi College stated there was “evidence of a concerning practice of social ostracism among students, often referred to as a ‘cancel culture.’” These kinds of cases have left many wondering why some students are, indeed, adopting this behaviour?

Professor McMahan believes the culture has a lot to do with “copycat” behaviour; student’s just following the crowd. He does, though, point out that it may have got worse because of technology: “I think it’s evolved [the culture], probably with a lot of influence from social media and the internet.”

The fear of being ‘cancelled’ on campus is also obviously evident. “Even faculty feel frightened and concerned that if they say the wrong thing, they’re going to be denounced,” says the professor.

Our conversation was then briefly interrupted when, to my surprise, the President of the College, Professor Helen Moore, entered the room. The two professors engaged in a warm conversation, and I was then introduced and offered yet another coffee and what looked like leftover Christmas cake. I accepted.

While Professor McMahan was making his second coffee, on a very snazzy looking coffee machine, it must be said. I noticed what his rather curious coffee of choice was: a large cappuccino with a splash of hot chocolate – a mocha is too sweet apparently; he prefers it this way.

After the brief intermission, the professor and I sat back down on those rather low, but quite comfy, sofas. We then started to discuss whether the rise of ‘cancel culture’ might start to put people off higher education in general.

“I think it’s already doing that,” says McMahan, “enrolments in American universities are diminishing.” The academic then tells me about how those on the right in America, particularly Donald Trump – whose name is said almost through gritted teeth – uses ‘cancel culture’ to reject “the intellectual credibility of academics.”

On this topic, the professor started to expand on how the likes of Donald Trump and Nigel Farage have taken advantage of those in society who’ve often felt left behind – like white men, for example. I wondered, was this something which could impact the culture on British university campuses, as the political gender divide widens and some men feel evermore disenfranchised?

“White male Anglo Saxons are more vulnerable to condemnation, they are more easily alienated and pushed into the arms of people on the right,” says the professor.

What we’re seeing happening now with ‘cancel culture’ is relatively new as a phenomenon. Whether this is down to social media’s enormous power to influence everyday life. Or just the rightly emboldened tackling centuries worth of societal injustices, it’s unknown. Whatever it is, however, it’s a major political, cultural, moral, and mental health issue.

“I think it’s a major threat [‘cancel culture’],” says McMahan. “Mainly because of the way it feeds and inflames its opponent.” The professor continues: “‘Cancel culture’ promotes and encourages the dangerous elements on the right [of politics]. It makes them more defensive and gives them a greater sense they’re right. [This is because] nobody likes to be told in vituperative terms that they’re immoral and horrible people.”

British university campuses face many difficult challenges in the coming years, not least with their financial struggles as inflation bites. With ‘cancel culture,’ however, there lies a challenge which is, perhaps, more nuanced and complicated than any other facing institutions.

Walking out the door of the college porters’ lodge I had entered not two hours earlier, the same thought I had before meeting the professor returned. This time, however, shaking hands goodbye with my host, apprehension overcame me. Apprehension over whether such institutions, which, indeed, have such an important responsibility in shaping the rhetoric of the future, can navigate a storm as complex and delicate in nature as ‘cancel culture.’ The fear is if they cannot contend with the issue, we could be staring down the barrel of a society with further division and greater discord.