From flower power to Reform: Are Gen Z reshaping politics?

While overall support for mainstream parties shrinks, the youth move to the fringe of the political spectrum.

“If you’re not a liberal at twenty, you have no heart; if you’re not a conservative at forty, you have no brain.” This famous line is often attributed to Winston Churchill. While there’s no evidence that those words ever came out of his mouth, it is certain that if he saw the latest UK general election results, he’d be turning in his grave.

Political beliefs amongst Gen Z are shifting. Yes, most young people remain progressive, and Labour is still the strongest party amongst the generation, backed by 43% of 18-29 year-olds in the general elections of July 2024.

What was a shocker, however, was polls showing that over 9% of Gen Z voted for a far-right party – Reform UK. While this may not seem like a lot to many, it is an sharp increase from the 2019 polls, where Nigel Farage’s party only secured 1% of votes amongst the young demographic.

What happened to the long hair, psychedelic colours, and flower power of the 60s? Why are we shifting to Farage, when we were the ones meant to fight for gender equality, free speech, and civil rights?

This news is not British-exclusive – it seems to be a trend in some European countries. In Germany, the results from the latest general elections in February this year revealed that 21% of Gen Z supported the far-right AfD (Alternative for Germany), a figure higher than the party’s overall national average. In France, Marine Le Pen and Jordan Bardella’s National Rally (RN) secured over 32% of the votes of under-34-year-olds in the 2024 European Parliament elections.

But this shift isn’t just on the right. Over the last two years, Zak Polanski’s Green Party presence has also experienced a significant increase among Gen Z. The Greens’ bet on renewable energy, social housing, raising the minimum wage and taxing the wealthy more contrasts with Reform’s plans on scrapping net zero, anti-immigration policies and foreign aid distribution cuts. In the elections, Polanski’s party quadrupled their 2019 support among 18-24-year-olds, securing 18% of the vote and surpassing Reform’s figures.

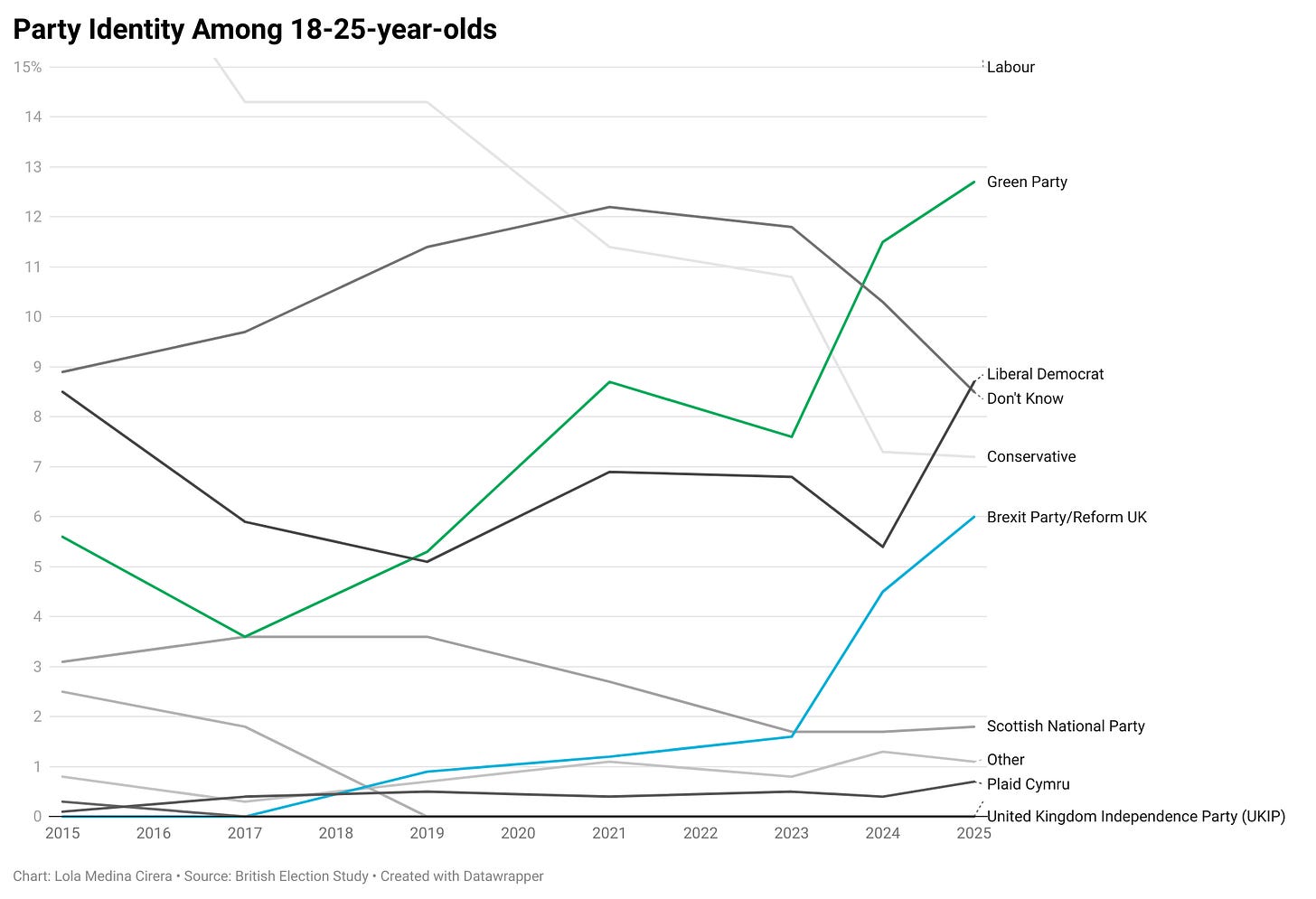

Both parties saw a surge in the elections over a year ago – and they have continued to rise. The latest British Election Study shows that nine months after the elections, the proportion of 18-25-year-olds identifying with Reform and the Green Party has increased by 33% and 10% respectively. While youth support for both parties is the highest it has ever been, support for centre parties is shrinking.

But, what is it that Gen Z are seeking in the Greens and Reform, that the Tories and Labour – which have dominated the political landscape for centuries – are failing to provide?

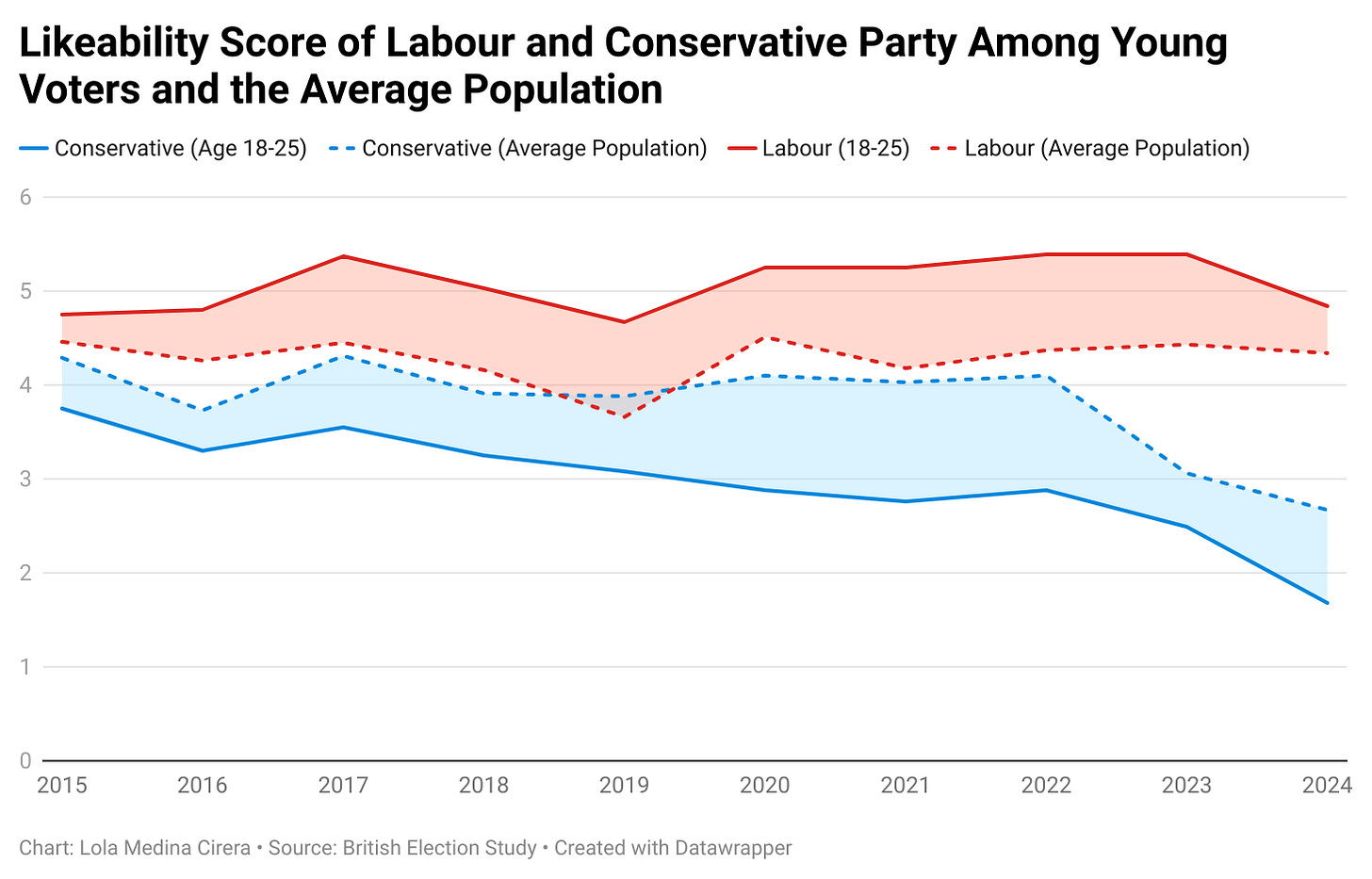

“Young people are deserting the mainstream”, explains Jon Wheatley, Politics professor at Oxford Brookes University. And Wheatley is right. Overall favourability ratings for both the Conservatives and Labour have sharply declined, with the drop in Conservative support starting in 2021 and Labour’s more recently. However, this trend is especially noticeable among 18-25-year-olds, who instead have turned to the fringes of the political spectrum

“This shift is due to two main reasons,” says Wheatley. First, both parties have failed to target Gen Z in their campaigns, assuming a low young turnout on election day. “Because it is higher amongst older people, policies tend to be dictated more by the interests of older generations,” Wheatley adds, leading to Gen Z feeling unrepresented by mainstream parties.

Second, there is a rising sentiment among younger voters that the main issues the country is facing aren’t being properly addressed. While this feeling is not exclusive to Gen Z, widely shared across different age groups, older generations tend to see their voting options limited to the two major parties – Labour and Conservatives. In contrast, younger voters are more exposed to non-mainstream party representatives, as these are increasingly active on social media – Gen Z’s natural habitat. “This makes young voters see them as potential options more than older people do,” explains Wheatley.

Gen Z wants a change. Struggling with unemployment, student debt, and the housing crisis, they feel let down. “Gen Z are the first generation that can not expect to be richer than their parents”, adds Wheatley. The old belief that getting a university degree guarantees a good job, a nice house, and decent pay, has expired.

After 14 years of Tory rule, Starmer’s party has so far failed to improve the living standards and future prospects for the younger demographic. “Part of the challenge for Labour is to provide economic growth and opportunity for younger people”, argues Wheatley. “But that is something that it has not been able to do so far”.

“The young need a clear vision”, he adds. Polanski’s Green Party seems to be an appealing alternative on the left for young voters, with this bold vision that Labour appears to lack. This need for a clear direction also explains the shifts on the right side of the spectrum. “Since the Conservatives seem to have become a soft imitation of Farage’s party, why would you vote for them if you can get the full thing with Reform?”, suggests Wheatley. Both the Greens and Reform have hit the nail on the head. Bold policies, promises for change, and addressing the segment of the population disappointed by the leaders who promise change but fail to deliver.

Social media has undoubtedly played a significant role in this political shift. Zak Polanski takes to the streets, microphone in hand, asking people about their views on national and global issues, from the cost-of-living crisis to the conflict in Gaza. He appears relatable, bold, and full of hope. Meanwhile, Farage’s populist discourse is paired with a rather unique and jovial social media presence – one that includes smoking, drinking pints, and signing football shirts. The Reform leader dominates the TikTok race, with over 1.4 million followers on the platform. Being one of Gen Z’s favourite sources for both entertainment and information, its role in reaching young voters is undeniable, which may be why Keir Starmer has recently launched his own TikTok account.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

But there is more to it than a clever social media strategy. The world’s richest man seems to have infiltrated British democracy. “The algorithm has to do a lot with Reform’s success”, says Wheatley, “Elon Musk is boosting the British right”. Through tailoring X’s algorithm, posts within the right-wing narrative are favoured. This algorithmic bias has led many left-wing voices and publications to leave X and migrate to Bluesky as an alternative platform.

Social media might be a potential driver of the gender difference in support for both parties. While among the general population, male voters tend to lean right and female voters towards the left, this gender gap is at its biggest amongst young people. YouGov polls from the 2024 elections show that, among 25-49-year-olds, support for Reform was 5% higher among men and for the Greens, 2% higher among women. But among Gen Z, women’s support for the Greens was nearly double that of men. As for Reform, women’s support was 6%, compared to 12% for men – again, doubling the ratio.

This pattern is not unique to the UK. A similar pattern shaped Germany’s February election results, where Die Linke, the leading left-wing party, received over double the votes from women. Conversely, the AfD gained more than double the support from male voters. “While it is hard to pinpoint the actual reason, a potential hypothesis is that younger men and younger women fall into different social media rabbit holes”, suggests Wheatley. Social media echo chambers could lead young men to be influenced by figures in the manosphere, such as Andrew Tate, vlogger Sneako, or former Fox News commentator Tucker Carlson. Under a sexist, nationalist discourse, these influencers promote traditional masculinity and self-reliance, while rejecting feminism, “woke” culture, and left-wing movements, arguing that these threaten Western values. Amplified by social media, these narratives could help explain why young men are drawn toward far-right ideologies, boosting support for Reform in the UK, the AfD in Germany, and National Rally in France.

While this shift amongst the ideologies of the youth is relatively recent, it is undeniable that Gen Z are not signing up for the two-party system that has defined British politics for centuries. They are deserting the mainstream. Now, the question is: will the mainstream do something about it?

Sharp analysis of the algorithmic radicalization loop here. The manosphere-to-Reform pipeline isnt accidental when you consider Musk's X algo tweaks basically function as a rightward conveyor belt. What caught my eye is the gender split data showing young men's support for Reform doubling young women's, which tracks with what I saw covering online political movements last year. The economic despair is real but social media echo chambers amplify it into ideological extremes ratehr than collective action. Gen Z got dealt a bad hand economically and TikTok turned it into tribal politics.