Is the motorsports industry truly creating space on track for women in Formula 1?

Could Netflix and a university extracurricular be part of the solution?

A $25.3 million dollar industry. 24 global Grand Prix over 10 months. Racing up to speeds of 234mph. There is truly no other sport like Formula 1.

This motorsport turned mega brand has long been renowned as a male dominated industry, with 70% of its fanbase comprising of men, as of 2022. In more recent history, the fan gender gap is now closing, with Netflix documentary series ‘Drive to Survive’ educating and inspiring women to join the F1 fan community. F1 CEO Stefano Domencialli noted that in 2024, female interest in motorsport had increased substantially, alongside new firsts for key team positions being taken up by women, such as HAAS’s Laura Müller becoming the first female race engineer in F1 history for the 2025 season. Its clear women want in on Formula One, but how are educational institutions responding to the interest, and what changes do the industry need to make to create more space for female engineers?

The UK is often regarded as the home of Formula One, with 7 of the 10 current teams on track based in and around Oxfordshire, also known as ‘Motorsport Valley’. Due to this, many UK universities are taking advantage of the graduate job opportunities and have become feeders for Formula One teams. Oxford Brookes University, and the University of Bath are both renowned for their networking connections within the industry, and alongside this, they both offer a Formula Student Team; an extracurricular opportunity to design, build and race an electric race car in competitions across Europe. One woman working in F1 commented: “Formula Student is, hands down, the absolute best work experience.”

Not only is Formula Student a brilliant experience, but it also encourages young women at university to get involved in motorsports and explore a career in it. Oxford Brookes Head of School for Engineering, and Principal Academic Adviser of Oxford Brookes Racing; Gordana Collier, believes it is vital to get girls involved “this is not like a garage where all the guys are doing all the work, and it's all men's things, there are so many different jobs”. Ms Collier recognises the value of female engineers within the team, and for Formula 1 altogether, believing “female engineers are wired differently, so they are bringing some fresh, different ideas. They are also positively affecting the dynamic of group work. So, there are all these things that having extra girls can help change the way the things are done.”

Another factor influencing women in motorsports is ‘Formula One: Drive to Survive’ which premiered in 2019 and has since run for over 7 seasons. It sells itself as an intense, intimate look behind the world of Formula One, following the lives of drivers, team principals and engineers. Drive to Survive (DTS) gave fans an insight many have never seen before. In 2023 the series reached 6.8 million viewers with 46% of those being women between the ages of 18-30, outstripping the sport itself, which recorded at only 30% female viewership. Team Bath Racing Electric (TBRe) Program Manager Abbey Marsden believes “it's so intrinsic to the women in motorsport movement now.”

In the 2024 season alone, female Formula One fan numbers increased up toto 41%, a 11% jump from the previous year. Abbey noted that “(DTS) made it easy to understand what F1 was and how it worked. It gave young women a space to learn all about this sport without, getting bullied for it, as nobody interested in the sport, wanted to teach them.” However, the DTS effect has been much broader in its impact. Speaking to another woman working within F1, she also commented “The sport has opened itself to other partnerships. The drivers have become brands themselves; you can consider them influencers. They all have YouTube channels. They all post what happens behind the scenes.” The series has encouraged the sport to become globally recognised, with, 53% of fans in the US citing ‘Drive to Survive’ as the reason behind their interest in the sport. Since its 2019 premiere, fan race attendance has increased from 4.2 million to a staggering 6.5 million in 2024, garnering even more financial support for the F1 economy.

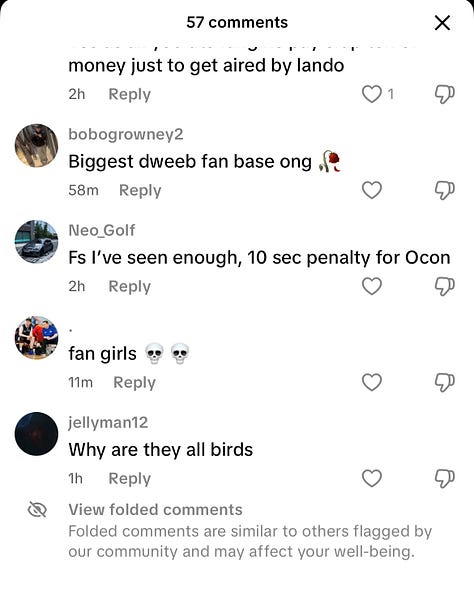

Although the industry is starting to progress, the fanbase is still holding back, with stigmatisation of female F1 fans online becoming common place. F1 broadcaster, Sky Sports, recently posted a series of interviews of female F1 fans recalling their favourite ‘memorable’ race moment on social media. The online comment section was littered with insults directed at the female fans, with criticisms like “this sport is finished,” “why are they all birds,” “hard watch,” “you just know they started watching F1 6 months ago” and “fan girls 💀”. Abbey reflected on this divide “unfortunately, I think some male fans got uncomfortable with all of these women coming together, and the feminine culturalization of something that is stereotypically and predominantly male.” This tight-knit female community is evident through Instagram accounts like ‘Girls Just Wanna F1’ (with 11.k followers), and ‘dishdoesf1’ (12.1k followers) which foster a community by bringing women and girls together to enjoy the sport.

With both extracurricular opportunities at university, and a fan community forming online, what is still holding women back? Abbey emphasises the disparity between men and women choosing engineering “for the women on our course, it's, a deeply proactive decision that they've made, whereas the 88% of men on my course are here because they were good at maths.” At Oxford Brookes Ms Collier feels similarly, citing the struggle for women to choose engineering as “families, do not advise their daughters to go and be engineers, so we do a lot of work trying to collaborate with schools to educate the children and then educate career advisors.”

In 2018 the overall employee gender split within F1 was 72% male and 28% female: this industry is clearly very largely dominated by men. In an effort to combat this, Formula 1 has been actively evolving over the last 7 years, supported by the ‘Formula 1 Diversity and Inclusion Working Group’ which aims “to work collaboratively to find ways to increase diversity across F1 and the wider motorsport industry”. The gender split in their 2024 Gender Pay Gap Report unveiled a 68% male, and 37% female split, a slight increase from previous years. Abbey is also joining Cadillac F1 in September and believes universities are pushing diversity, but the real issues are still present in the workplace “I did three job interviews, and I was the only woman at all three of them. So, it’s a funny dichotomy that almost half of F1 viewers are women. However, I am still the only one in the room.”

Unconscious bias clearly still exists within motorsports engineering positions, a key example being the 20% average gender pay gap experienced between men and women in motorsports as reported by the F1 Gender Pay Gap Report 2024. Abbey commented on one experience in the workplace, recalling how her male colleague “was given a lot more responsibility, and definitely a lot more praise than I was, or at the very least, the expectation that the quality of his work was always going to be higher than mine”, even though they were both doing the same job.

In the educational sphere, Ms Collier believes part of the solution lies in including male engineers in the conversation “we need to train both boys and girls, because they need to learn how to live (& work) in this environment, together and collaborate.” This point was echoed by Abbey, noting that “you need men to also be engaged, because you can't break the glass ceiling in one direction.” Not only is educating boys important, but it’s also about what stage do educational institutions introduce careers like motorsports engineering to young girls? “It needs to start from primary school,” insists Ms Collier, “our job is we need to really make motorsport not look like a male discipline. That's the only way.” Abbey has the same belief “diversity in motorsport, begins with convincing young women that it's a space for them in the first place.” As young female engineers, it is also vital to set boundaries, and allow yourself to be confident, Abbey jokingly uses the example of “always apply with the confidence of a white man who's not qualified for the job. If they are not fully qualified, they will apply anyway, whereas, stereotypically, women will only apply when they 500% fit the role.”

Universities also need to adapt how they present working in motorsports for women; Abbey commented that “there always seems to be a lot of initiatives to get women into the course, but then once they’re there, it feels like, oh, a box ticked, we’ve got the women now.” After recruiting female students to join the course, universities need to recognise the reality of the diversity gap within the motorsport industry and aptly equip female engineers with the tools to approach any situation. Abbey added “the next step is to not send them off into the workplace with a rose-tinted idea of what it's like, because it is, unfortunately, a lot less forgiving than university portrays it as.”

There is clearly no simple fix for gender bias within motorsports, however the dial is shifting, with leaders of industry actively pushing for diversity. After listening to these inspirational women, it is clear they are proactively discussing solutions to engage girls from a young age and continuing to help them believe there is a space for them within Formula 1.

As a final takeaway for any young women interested in working in motorsports, Abbey offers some invaluable advice. “If you've got an offer from a team or a department, where there's been talk of holding a bias against women, there is absolutely nothing wrong with saying no, because it is not the be all and end all. There is a team (for you). There is a department who will, and who do understand what needs to be done in the industry.”