Losing a grandparent in your 20s

It seems like a backwards statement, but it is a true honour.

There’s that ancient adage that bad news comes when you least expect it.

For me, it came barrelling down the metaphorical tracks and smacked the breath out of me at 07:46 on a Wednesday morning.

Despite a tremendously positive prognosis, my grandfather had suddenly passed.

For an individual to lose a grandparent in your 20s, as I have been unfortunate enough to have been on the receiving end of twice to date, is an entirely new phenomenon for a person to grasp.

As you age and mature, you inevitably become aware that everyone you love is ageing with you, but the concept of losing those people doesn’t tend to confront you until it happens.

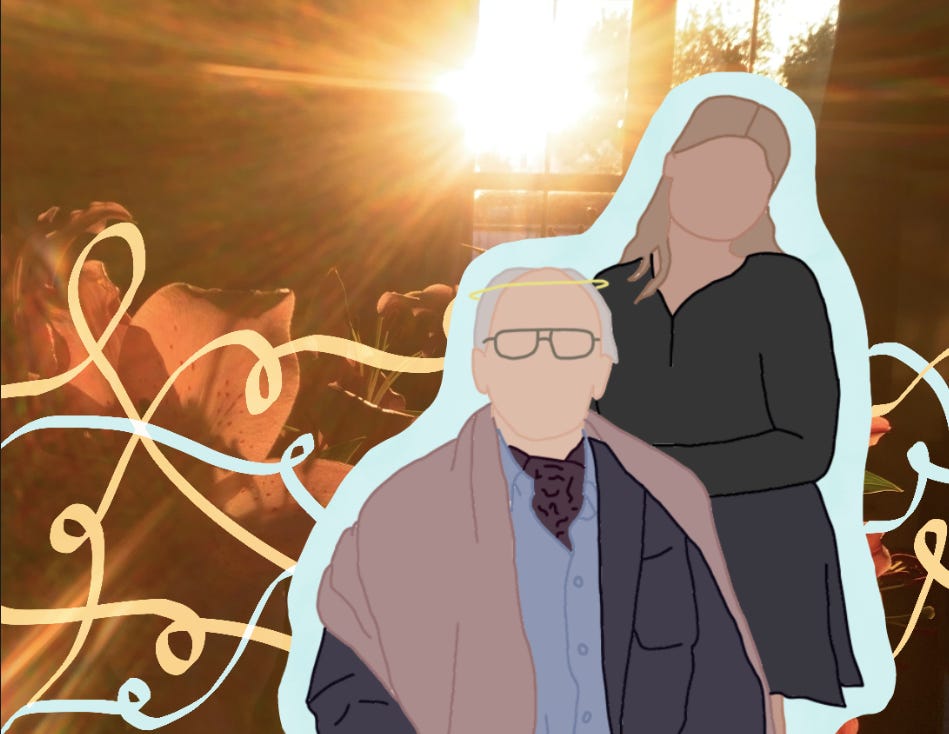

My grandad Peter was a stoic, well dressed military retiree. When my mum became swamped as the head of CSI for a children’s home case in Jersey, my grandad came over to the island to provide much needed childcare for a then 6-year-old me and my 4-year old-brother.

What I didn’t realise till much later is that by coming to Jersey and becoming a full time third parent for months was not only life saving for my parents and us, but for my grandad too. He had recently lost my Granny to cancer, and was stumbling through life without aim, and heartbreakingly, without much motivation to keep going.

Looking back, this mutual agreement that came about because of tragedy on both ends, was a blessing.

My brother and I were given an entirely unique opportunity to know our grandad, who lived far away in Portsmouth.

We learnt his quirks, his love of ‘Yorkie’ bars and Cadbury fruit and nut - chocolates it later transpired that he bought because one was stamped ‘not for girls’, and the other unappealing to small, fruit-avoidant children.

We learnt that the man could rouse himself from the deepest of slumbers to scold us if we went near the remote as he snoozed his way through vivid war documentaries. We learnt his smell, comforting and soft, peppered with the smell of ink and newspaper from his daily crosswords.

We learnt to associate him with the Kinder Eggs he always bought us in the walk home from school, and the perfected dexterity in which he cooked his ‘famous’ spaghetti bolognaise.

We learnt that he could be persuaded to sing, old naval tunes, which ricochet and echoed off the walls in a deep, calming tone, and could sooth overexcited youngsters.

We learnt his booming laugh, tinged with years of smoking. His annunciation and his incredibly specific voice of incredulity, reserved for the antics of small grandchildren. His eternally perfected cravat, worn 22 hours a day, every day.

We learnt his kindness.

Years later, after he had been ill for some time, I saw him at a family garden party. Despite his fragility, he sat tall in his chair, that same perfectly straight cravat, a pint in his hand, and I realised that my grandad had not changed. Perhaps he couldn’t have run around after little feet, but his laugh and his humour and his voice was the same. I think that was the last time I saw my grandad as I knew him. The illness took away his sense of self a lot of the time, but he still knew me, and I him, and to me, he’s still as kind and lovely as he always was.

Losing a grandparent in your 20s is a bittersweet honour. The sadness comes from the fact that you lose them physically, that that person is no longer there.

The honour is that you knew them when you were old enough to know them properly.

I was honoured to not only know my grandad, but recognise in exact clarity his tribulations and struggles, which made him all the more incredible.

I think there’s a certain stigma around grandparents - the age gap that is slightly too large for generational understanding - but I’m of the opinion that it’s somewhat of a joy to have that age gap - or more specifically, to understand it. There becomes a mutual understanding of growth between the grandchild and the grandparent, and a mutual grown-up respect that comes with it.

So, there is the beauty within the ugly sadness that is grief. Grief is a warping, crushing, cruel and yet inevitable element of being alive. But, as a talented poet Shannon Lee Berry once wrote, in a poem that has stuck with me for over a decade, ‘when I turned to face grief I saw that it was just love in a heavy coat’, and my goodness did she hit the proverbial nail right on its proverbial head.

That is exactly what grief is, so isn’t it inevitable that ever-enduring-humans should be able to find some odd semblance of joy within the shadows?

To put it quite ineloquently, losing a grandparent in your 20s completely and utterly sucks. But I am human, and I have loved and continue to love, so, I am also determined to see some sort of subverted beauty in it.

I am heartbroken and grieving, and will be for some time. But I am also incredibly lucky, and in fact, the luck I feel that I knew my grandad - really knew my grandad - is something that will last long after the sharp grief fades to a dull, bittersweet ache.

This article is dedicated in deeply loving memory to Lt Peter Bolam RN, 1939-2024.