More Crashes in Urban Centres, More Deaths in the Countryside

What the Numbers Quietly Reveal

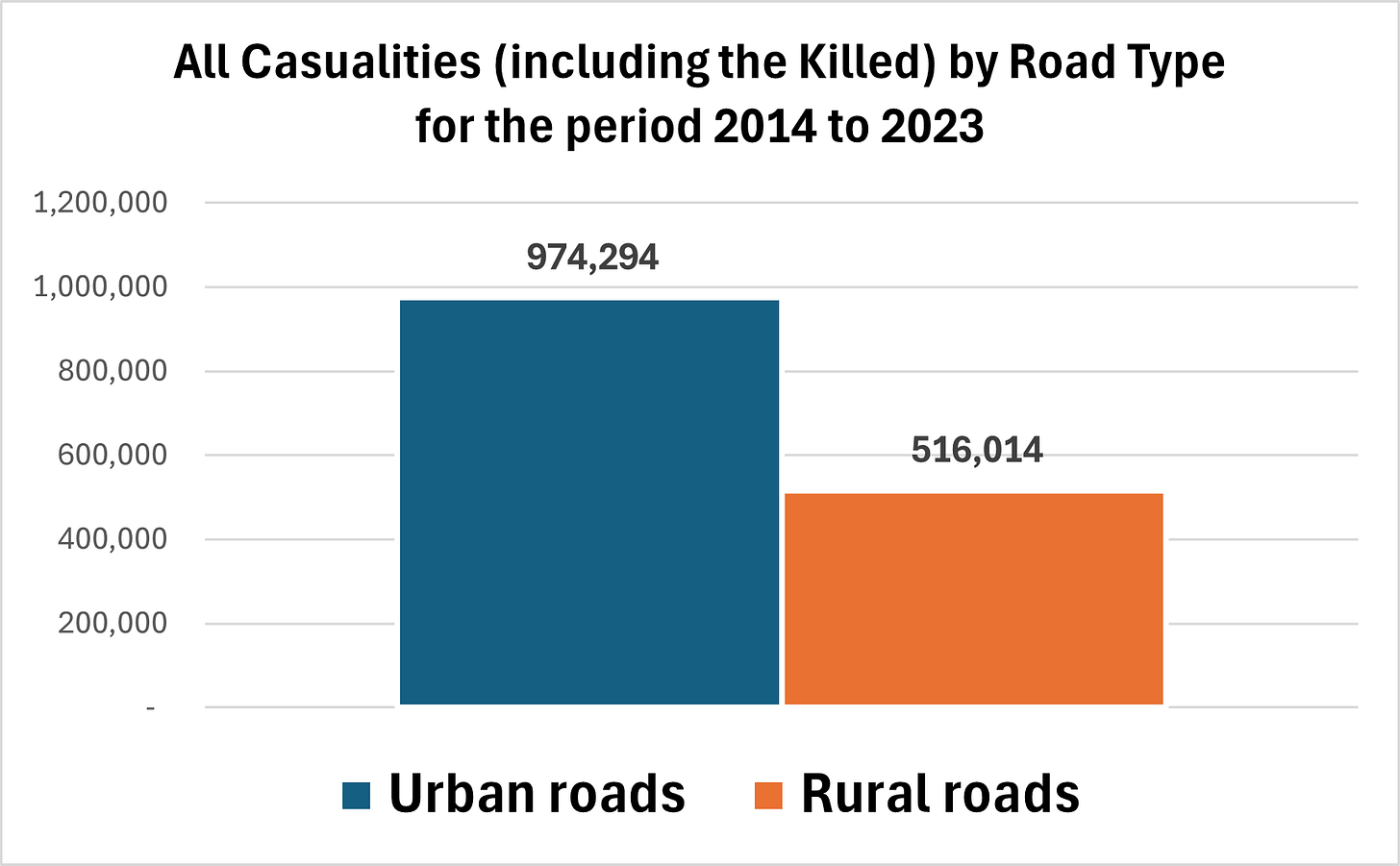

According to the data released by the UK Department for Transport, more than 1.5 million people were reported as casualties in road traffic collisions in the decade leading up to 2023. This total includes a full spectrum of casualties ranging from those who sustained minor injuries to those who sadly lost their lives, recorded both in urban and rural areas. The geography, however, reveals something very disturbing. While urban areas see more collisions overall, it is the rural roads that account for most of the deaths.

Of the 1.5 million recorded casualties, only 1.09%, approximately 16,979 people, died because of their injuries. This translates into an average of 2.53 deaths per 100,000 people per year.

The World Health Organisation reveals that the average across Europe is 7 deaths per 100,000 people per year which puts the United Kingdom fatality figures significantly below the regional average.

This is attributed to a system that is working, with effective emergency response, quality healthcare, and better safety enforcement.

While urban roads accounted for 65% of all casualties, only 38% of those were fatalities. On the other hand, rural roads accounted for 62% of the fatalities despite seeing far fewer collisions overall. This pattern raises a simple but important question: why are people more likely to die on rural roads?

According to a 2017 Rural Roads report by The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA), higher speeds and longer response times are some of the possible explanations for more deaths reported on Rural roads. This further states that the national speed limit on rural single carriageway roads in the UK is 60 mph, which is significantly higher than the default 30 mph in urban areas.

While precise response times are not publicly reported by the region, UK’s Road Safety Observatory confirms that emergency services take longer to reach crash victims in rural areas than in cities. This delay, combined with higher driving speeds, make rural collisions far more likely to result in death with the most affected age group being 30-39 years.

Tenzi Lama 56, a gate line assistant for Great Western Railways, in an interview said, “I one time witnessed a rock falling on to a car ahead of me while we drove with my son in a tourist area Lake District. So, these unforeseen conditions and abrupt weather changes also make collisions in the rural areas fatal. It is very sad that emergency response services took much longer than normal to arrive at the scene, we were forced to stayed there for hours and hours as we could not go ahead or behind”.

“We grew frustrated, and tension was building amongst us, with uncertainty of the future, wondering if rocks would do the same to us. I had to soothe my son, but I was scared myself.”

It is on this note that Lama, urged the government to improve road emergency response especially in the rural areas by constructing equipped health centres on every isolated road.

The most immediate insight from Lama is rural road safety requires more attention, investment in emergency medical coverage, signage, lighting, and speed enforcement outside the cities to save lives.

In Berkshire, there is already momentum in some areas, with the borough local council advocating for road redesign schemes, speed limit change, speed awareness courses, speed fines in a way to cut incidents on roads.

Despite a national trend of decline, new research has revealed a slight uptick in the number of road traffic accidents that Thames Valley Police were called to assist with in the year ending August 2023.This data was compiled by Lime Solicitors who conducted a comprehensive Freedom of Information (FOI) request to various Police Forces across England.

The solicitors firm found that Thames Valley Police officers dealt with 8,771 road traffic accidents, a slight increase from the 8,722 in the preceding year.

Julian Ranzly, 60, a renowned taxi driver in Reading for over 20 years, in an interview with me said, “rural roads need to be made wider than they always have been to allow for safe passage of traffic either way, consider putting street lights on rural roads and added that insurance companies should introduce mandatory black boxes into young and middle aged drivers’ cars to ensure adherence to speed limits and safer driving”.

“I got involved in an incident that saw my car overturn, but it wasn’t my making, the car from behind me, burst its tires and rammed into mine good enough my seat belt was fastened, sadly the girl in the other car ended up in the woods.” he added.

Lama advises young people to always wear their seat belts and to check the cars for main safety areas before trips.

Conclusion

Regardless of the rural fatality rate, a 1.09% UK fatality rate from all road collisions for over a decade is no small feat and points to decades of investment in safer vehicles, mandatory seatbelt use, public education campaigns, and the NHS’s trauma response capacity which cannot be overlooked. There is, however, no room for complacency because losing nearly 17,000 people regardless of how long it takes is a huge cost emotionally, mentally, financially and socially to bear.

Everybody is a candidate of a statistic, and every dataset is a representation of choices, conditions, and consequences. These show that while cities are crash-prone, they’re also safer in ways that matter most. And rural areas, with all their beauty and quiet, can be deadly when something goes wrong.

The responsibility upon everyone isn’t just to analyse the numbers, but to act on them before another 17,000 lives are lost to silence and geography.