Oxford Brookes' celebration of the World Lemur Day links science, culture, and classrooms in Madagascar

Oxford Brookes’ annual festival bridges conservation science with Malagasy culture, showing how classrooms can help save forests.

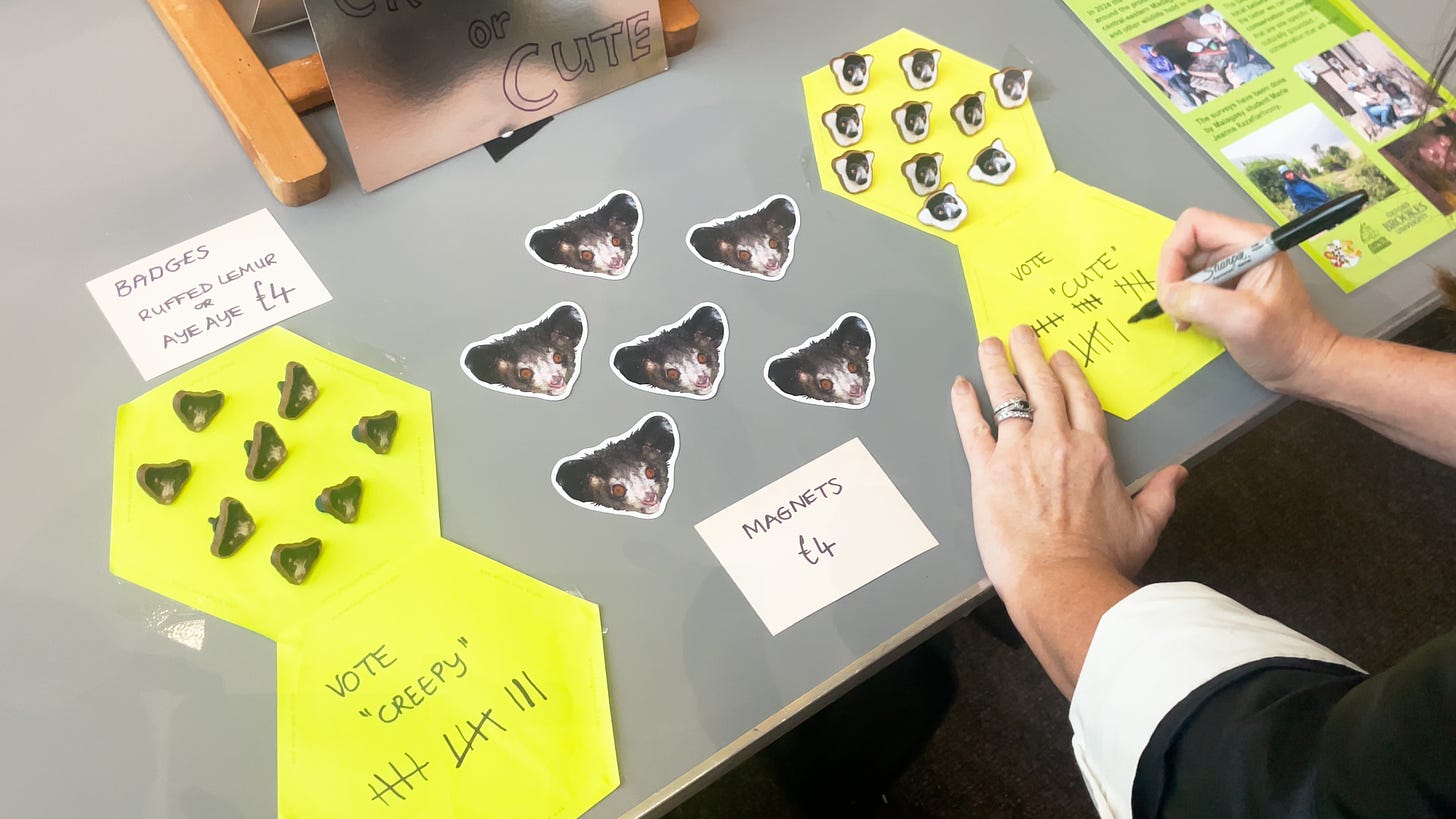

Every year on the last Friday of October, conservationists mark World Lemur Day; and at Oxford Brookes University, the occasion turns into a festival that blurs the line between science fair and cultural fair. This year’s theme, “Creepy vs Cute,” asked visitors to think again about the animals that make Madagascar famous.

Organised by the Nocturnal Primate Research Group, the event showcased student projects, a craft market sourced from Malagasy villages, and new research on how people perceive lemurs, especially the aye-aye.

Professor Giuseppe Donati, who leads the university’s Master’s of Science (MSc) in Primate Conservation and Master’s of Research (MRes) in Primatology and Conservation, says lemurs aren’t just icons, they are “gardeners” of the forest. Current studies continue to show many lemur species disperse seeds that help regenerate native trees; losing lemurs would accelerate the decline of already fragmented forests.

Recent studies by Professor Donati and his colleagues show that both day-active and night-active lemurs play a vital role in maintaining the diversity of Madagascar’s forests, dispersing seeds that allow damaged habitats to recover. Their work also highlights how local traditions associate “taboos” to certain species that often determines whether communities protect or persecute them.

But biology is only half the story. New findings led by Oxford Brookes’ researchers argue that conservation must respect local beliefs about the aye-aye, the largest nocturnal primate. Long cast as a “bad omen” in some places, yet treated as a sacred being and even given funerary rites in others. The team calls for “context-sensitive” outreach that works with, not against, Malagasy cultural frameworks—a message organisers wove into the festival’s talks and family activities.

Dr Claire Cardinal, a visiting research fellow, recently back from north-west Madagascar, coordinated a stall of handmade goods to raise money for a partner primary school. In many rural districts in Madagascar, families have to help cover teacher salaries and materials. Proceeds from the festival will support lessons on biodiversity so that children learn why lemurs—and forests—matter.

Students, including Lesley McIlroy and Linus Coppersthwaite, presented projects on lemur activity patterns and the cultural perception of aye-aye. Their message was clear: science, culture and education have to move together if conservation is to work on the ground.

World Lemur Day events, together with partner zoos, help generate small but steady funds that support school programmes and strengthen research efforts in the field. Organisers say any money raised will contribute to monitoring lemur populations, advancing research into their behaviours, habitats and genomics, providing field equipment for Malagasy teams, supporting Malagasy research students, and working with local communities to share knowledge and raise awareness about conservation.