Patriotism vs progression: what is ‘British identity’?

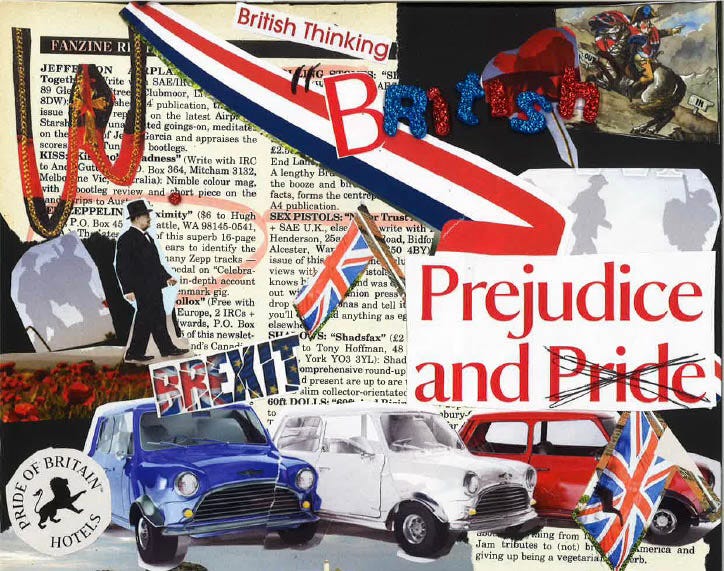

How can art be used to express the complex landscape of British national identity?

British national identity has reached a fragile tipping point in today’s polarised political climate- in the latest census, only 54.8% of the population selected the national identity ‘British’. Polarising politics has provoked generational divides over what should be deemed ‘British values’, causing cracks to appear in the foundations of how we view our own identities.

Creative expressions of national identity

One way to express feelings of identity and belonging, or lack thereof, is through art. This is a key theme within Oxford’s Turner Prize 2024 shortlisted Ashmolean NOW exhibition ‘To Those Sitting in Darkness’ by London-based artist Pio Abad. The collection expresses colonial history and cultural loss in a visual and understandable way through ‘poetic, personal and political’ pieces which criticise the way British institutions collect artefacts.

The exhibition highlights wider issues in contemporary society about the difficulties in balancing feelings of patriotism and national pride with awareness of Britain’s imperial past and striving for a more carefully considered future.

Venessa K Parker, a British contemporary artist experienced in exploring life, identity, and resilience through her work, explained how the individualistic nature of national identity means it ‘can be so bespoke to different people’.

‘I wanted to celebrate a part of me, of my identity. My grandparents came over from Dominica and St Lucia in the 50s… over the years I’ve learnt about the countries and their legacies… but I was just thinking it’s not something I have seen portrayed very much in art.’

‘I just really wanted to show a bit of pride for where my ancestors come from and have that reflected in my art’, achieving this through her collection with Caribbean clothing company Sakafet London in celebration of Dominican Independence Day. Sharing an alternative perspective on what it means to be British today, Parker explained that ‘although it's not what some people would think of as inherently British, I think it is, because those countries helped to fund the industrial revolution and to rebuild Britain after the war. I think it’s so intertwined that there’s no way you can say that it’s not British’.

Art ‘leaves space for people to create their own narratives’ around their individual national identity, with the two being constantly intertwined.

British identity in 2024 is a ‘melting pot’ of aspects from countless other cultures, according to Parker, which could explain generational differences in feelings of pride vs detachment from nationalist values.

Perhaps a solution to growing divides is to embrace identity’s individual nature to each person, accepting that there is no singular definition of ‘British’.

What does research tell us about British identity?

Dr Claudia Lueders, Lecturer in Politics at Oxford Brookes University who has extensively researched national identity, echoed this idea of British identity being difficult to define, explaining how ‘people always assume it's something very homogeneous, but it's actually so much more diverse and complex’.

She went on to suggest that over the last 10-20 years, the devolution of power to national governments in Scotland and Northern Ireland and the highly divisive political aftermath of Brexit were ‘driving forces’ in changing perceptions of national identity. Existing cultural divisions were then deepened by the global Covid-19 pandemic, which ‘surfaced a lot of inequalities within British society’, leading to increased introspection about Britain’s colonial history and ‘how fragile, actually, society is’.

‘So how do we deal with the colonial past? Right? And obviously, there's kind of a divide between people who think we should celebrate it. Who should be proud about the history. And then other people saying, no, we need to be much more critical. And we really need to reflect. And we need to think about how do we deal with this?… There's a lot of tendencies to decolonize the curriculum in schools and universities, and actually moving away from the dominance of white men.’

‘So how do we teach this history to children in schools at universities? How do we teach it to tourists that are coming to Britain? And how do we navigate that kind of history?’

According to Dr Lueders, there is an ‘ethnic’ and a ‘civic’ understanding of national identity and belonging, with ethnic definitions often requiring individuals to be born in the UK, and civic understanding of speaking the English language and identifying with the laws of British society. She added that data shows ‘distinctions in between younger and older generations as well… We see that younger members of society tend to identify more as British compared to older people of society who identify more English’.

Back in 2011, a national identity Census question was introduced, due to ‘increased interest in national consciousness and a demand for people to be able to acknowledge their national identity’, according to the ONS. As noted by Dr Lueders, the timing of this new question is significant, because it captures data from a key moment in politics following the Devolution movement, when nationalist values were on the rise in several British nations. This can then be compared with data from the post-Brexit 2021 Census, highlighting the fluidity of national identity during a contentious political period.

‘What we already see is that there is actually a decline in people who consider themselves solely English, and we do have an increase in people who consider themselves British rather than English’ Dr Lueders summarised.

Is it possible to be both patriotic and hold liberal political views?

The answer is more complex than a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

‘What we see in the studies is that people who are liberal tend to be, I wouldn't say less patriotic, but they have a different understanding of national identity’. Dr Lueders went on to suggest those with more Conservative beliefs tend to hold an ‘ethnic’ interpretation of national identity, whereas a Liberal would hold a ‘civic understanding’. Therefore, there are more factors to consider than at first glance.

At a time when politics is more fragmented and misleading than ever, art as a medium for expressing cultural memory and voices has arguably never been more important. Have we lost touch with the true meaning of ‘British values’?