Percentage of NHS staff absences attributed to mental health at their highest level since the pandemic

They take care of our wellbeing - but what about their own?

In March 2020, and for the following 10 weeks, Britons took to their doorsteps to applaud our healthcare workers. However strange the ritual may seem now, it was a true moment of unification in uncertain times, demonstrating wide-spread gratitude for the NHS on a scale never seen before. Not only did we all seem to recognise the physical health risks staff faced during Covid, but also the mental health impacts of being at the frontlines of tackling a global pandemic. Over five and a half years later, with lockdowns a distant memory and face masks few-and-far between, much of the world has moved on - but statistics suggest it is time to consider that not everyone has recovered, with ill mental health continuing for healthcare workers.

In fact, examining the NHS’s sickness absence data reveals that mental health remains a consistent problem, with ‘anxiety/stress/depression/other psychiatric illnesses’ being the overall top reason for absences every month for the last two years, from July 2023 to July 2025. Moreover, the average percentage of absences due to psychiatric illnesses across all staff groups in the NHS in England is actually now at its highest level since the pandemic, rising continuously from January 2025 onwards to account for 30.3% of overall absences by July 2025 (see graph below).

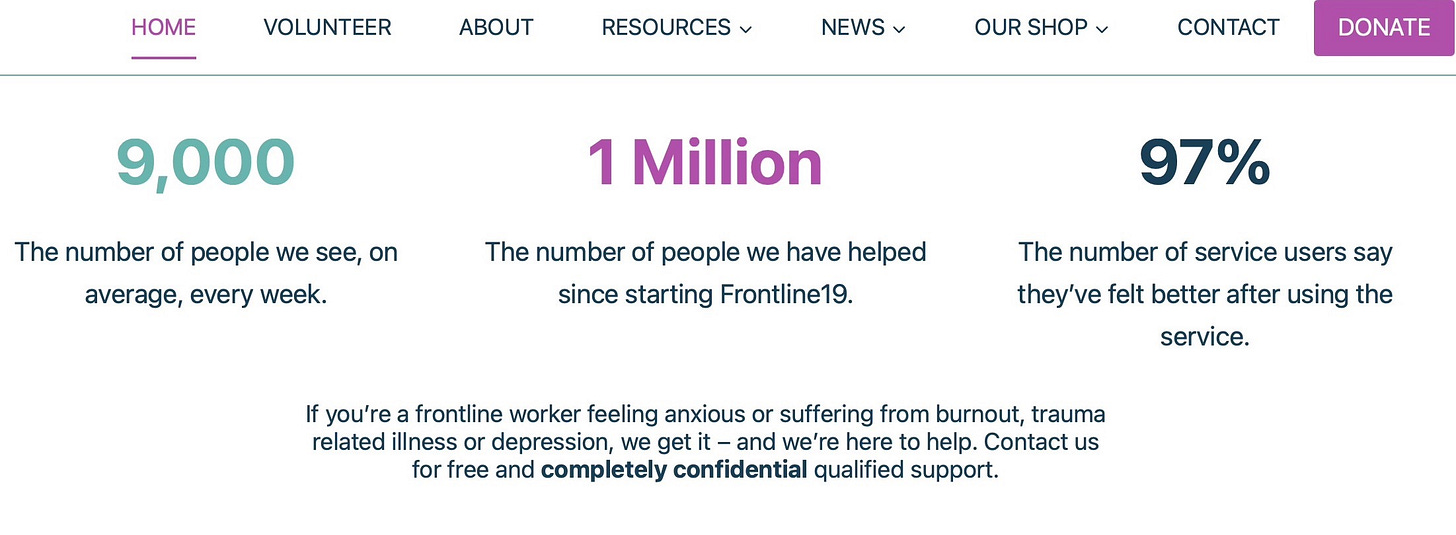

With a closer look though, we can see that mental health problems for NHS staff are not just another residual effect of the pandemic, with absence rates at 27.1% in July 2019 - long before the outbreak of Covid in the UK. This is a sentiment similarly highlighted by Samantha Wathen, Chief Operating and Communications Officer at the non-profit organisation Frontline19, which provides free psychological support and counselling to frontline workers.

Samantha explains that “workers were already flagging before the Covid pandemic hit”, a result of “the cumulative effect of years of underfunding and understaffing”, adding that “the NHS has been in a perpetual state of crisis now, not only over winter when it gets most press attention, [but] for many, many years”.

She says that these working conditions mean staff have “no time to pause” - let alone truly heal from the trauma of pandemic work, with PTSD now “alarmingly common” - and as a result leaves “staff far more open to litigation now too due to rota gaps, tiredness and mistakes sadly being inevitable to some extent”.

With workers lacking appropriate resources in circumstances out of their control, Samantha explains that staff consequently face “the issue of moral distress”, disheartened by their inability to “deliver the level of care they would wish or that is required”. Compounded by the fact that staff are often blamed for the problems that arise as a result of understaffing and underfunding, she claims that “all these effects add up to chronically low morale in the health service”.

Her observations are undoubtedly reflected by the bleak picture painted by the 2024 NHS staff survey national results, where just 34.01% of respondents said there are enough staff at their organisation to do their job properly and 41.92% not feeling they had the adequate materials, supplies and equipment to do so either. It therefore becomes unsurprising that it also revealed 34.07% found their work to be emotionally exhausting and that 28.83% often think about leaving the NHS.

These results come from a range of NHS staff groups, further supporting Samantha’s view that the effects of understaffing and underfunding - “exacerbated” by Covid - have contributed to morale problems and a “significant prevalence of mental ill health amongst all sections of the workforce.”

Though this reflection is true, with an average psychiatric illness absence rate of 26.8% across all staff groups from July 2023 to July 2025, it is also worth noting that some groups’ mental health absence rates are particularly high, as demonstrated by the graph above. For instance, psychiatric illnesses make up a much larger proportion of absences in the NHS infrastructure support groups, causing 37.7% of absences for Managers, 37.5% for Senior managers and 34.3% for Central functions staff, compared with an average rate of 13% for HCHS Year 1 Foundation Doctors.

Nevertheless, it is obvious that as the government attempts to deliver on its manifesto promise of building ‘an NHS fit for the future’, the issue of poor mental health for all staff groups in the organisation must be tackled. To do so, Samantha says it is vital for them “to acknowledge that healthcare workers are human, and that they are basically holding up the system on their own.”

She adds that it is important to recognise that NHS workers’ jobs can be intensely stressful and emotionally draining just by their nature, explaining that “even in a well-run, well-staffed and well-funded system, healthcare workers by the very nature of their role are seeing potentially traumatic incidents, sometimes on a daily basis.”

“[The] government must both acknowledge the long term effects of working in this environment on the workers and support them appropriately – whilst simultaneously committing to real change that improves the service for both staff and patients”

Samantha’s call to action from the government is even more urgent now given the complications to wellbeing infrastructure for NHS staff caused by the abolition of NHS England (NHSE) - the administrative body that oversees the NHS - in March 2025.

The Public Accounts Committee (PAC), which looks at the value for money of government projects, has already stressed ‘the great uncertainty’ that the abolition has caused for people across the healthcare system, outlining their concerns over the impact of this uncertainty on staff and patients in an article released in May this year.

The PAC also highlighted that the government has still not detailed how such a ‘major structural and operational change’ would go on to ‘impact key services and targets to improve patient care’, alongside a lack of clarification on how the NHSE’s ‘institutional knowledge’ would be preserved as it merges back into the Department of Health and Social Care.

Although the select committee raised numerous issues with the lack of details surrounding the NHSE’s abolition, what went unmentioned in the PAC’s article - and indeed in wider conversations on the issue - is that the mandatory requirement of the government and the NHS to provide staff with wellbeing services has also in effect been abolished, something Samantha claims “happened purposefully quietly and is a shameful act”.

She explained that whilst previous wellbeing initiatives were “generally inadequate and, in some cases, downright insulting” (mentioning yoga sessions as one example of this) at least then “there was some effort made”. For Samantha, the current lack of explicit provisions for these initiatives for staff sends a disheartening message that “staff are not valued” and that “their mental health is not important”.

Moving forward, to fulfil the duty of care they have for workers, she says instead of relying on “non-profits like us to pick up all the pieces”, the NHS and government “need to commit to a proper support system that offers meaningful interventions via self-referral”.

Samantha also suggests that this should also be in the form of “decent in-house provision”, where support is “embedded into their [staff’s] work experience” and clearly signposted so workers know where they can access help.

Hearing Samantha’s insights alongside what the NHS digital data shows us, it is clear that, regardless of the cause, the persistent and rising issue of ill mental health within the NHS workforce must be acknowledged - and moreover addressed - by government action. Without clear long-term provisions that commit to ensuring the wellbeing of our healthcare workers, how can we ever expect them to take care of the wellbeing of an entire nation?

To find out more about Frontline19’s work, visit: https://frontline19.com

Amazing article Skye!