The confession booth of the internet

Why survivors of sexual abuse are sharing their traumas with thousands of strangers on TikTok

Trigger warning: sexual assault, violence, explicit content.

Music is blasting through the speakers; people are jumping and roaming around the house, singing along.

Cups and bottles of alcohol are scattered everywhere. While the girl is waiting in the queue for the bathroom, a guy approaches her and starts flirting. She kindly explains she is not interested and makes her way into the restroom.

Before the girl closes the door, the guy bursts in and locks the door. He pushes her and as she falls. She tries to scream for help, but the music is too loud.

Ignoring her shouting and defiance, he proceeds to rape her. When he’s done, he leaves the girl lying on the bathroom floor crying and returns to the party.

This is the disturbing story Jade, 19 — the alias name she is referred to in this article, as she chose to remain anonymous — shared with Hybrid Magazine in an interview earlier this month.

When asked about the legal actions undergone after the incident, Jade confessed that she felt empowered by TikTok creators who ‘shared their trauma with thousands of strangers on the internet’ to seek professional help.

‘I feel like at the time I had been silenced for too long, and speaking my truth finally gave me a sense of liberation, a feeling I had only heard about in videos on TikTok’, she said. ‘I didn’t think I would find a glimpse of hope on the internet of all places, considering how the general public sees social media as the root of all problems of today’s society.’

Major trends tackling the subject of sex crime circulate on TikTok all year round — from showing outfits worn while being assaulted and celebrating Denim Day, to exposing evidence of abuse under fragments of famous songs — proving the platform is, in fact, driving the latest wave of sexual assault activism.

By allowing users to post short videos of up to 3 minutes, TikTok has developed into the perfect hub for virality, creating the strongest sense of community within its users compared to other top social and video platforms.

The safe space creators and users have built, where they can express themselves openly without the imminent fear of judgement, has encouraged victims of sexual assault to step out and talk about their experience.

University of Sydney Professor Catherine Lumby argues that such trends allow victims to ‘tell their stories in a collective way rather than in single file, which is what they were forced to do in the past — to police, or friends and family — which often brought a sense of isolation for them.’

While we’ve already seen people raising awareness of sexual assault by taking part in social media trends, such as the infamous Twitter #MeToo and #NotOkay hashtags, the difference TikTok makes is that it reaches a much younger audience.

‘Gen Z is probably the most receptive generation when it comes to actively fight against assault’, says Jen, who argues that the payoff of seeing victims raise awareness on the platform results in them later helping to save a life by stepping out and taking action when they come across such a situation. This is what experts call a bystander situation.

Katherine Hosie, an intern researcher at Reach3 Insights, a global research consultancy, argued that for the predominantly young audience ‘personal is political’. Unlike other social media platforms, on TikTok, one would not find performative activism, as Gen Z users who make up for the majority of the crowd are “willing to enact tangible change.’

Last year, digital activism took the app by storm during the Black Live Matter protests, as creators were using the platform to educate people on racial injustice and to share unseen images from protests. The hashtag #blacklivesmatter currently has 29.4 billion views, and the number is growing. It is safe to say it comes as no surprise then that assault survivors would seek justice on TikTok.

The main hashtags used by creators under their videos are #sexualassaultawareness and #sexualassaultsurvivors and they now have over 231 million views altogether, and the numbers are growing. When asked why, Jade explained: ‘I think users value the opportunity of speaking their minds without being judged. Usually, you would open the app and stumble across creators who make self-deprecating jokes or show their crazy collection of back scratchers and not find any negative comments.’

A Nielsen authenticity study commissioned this year by TikTok found out that 59 per cent of users feel a sense of community, which Jade interpreted as a result of people taking part in trends by either posting a video themselves or commenting. Basically, of all places on the internet, TikTok seems to be the only one where subjects of the general debate such as rape culture appear to be more often than not destigmatized.

Meet English singer Sam Fender and his now TikTok famous ‘Seventeen Going Under’, a song used by survivors to speak their truth upon experiencing violence of all sorts, of which domestic and sexual seem to be prevalent. Almost 172,000 videos have been posted, with victims sharing then-and-now comparisons of them and their abuser or graphic, explicit pictures of body injuries while singing along to lyrics, ‘I was far too scared to hit him/But I would hit him in a heartbeat now/That’s the thing with anger/It begs to stick around’.

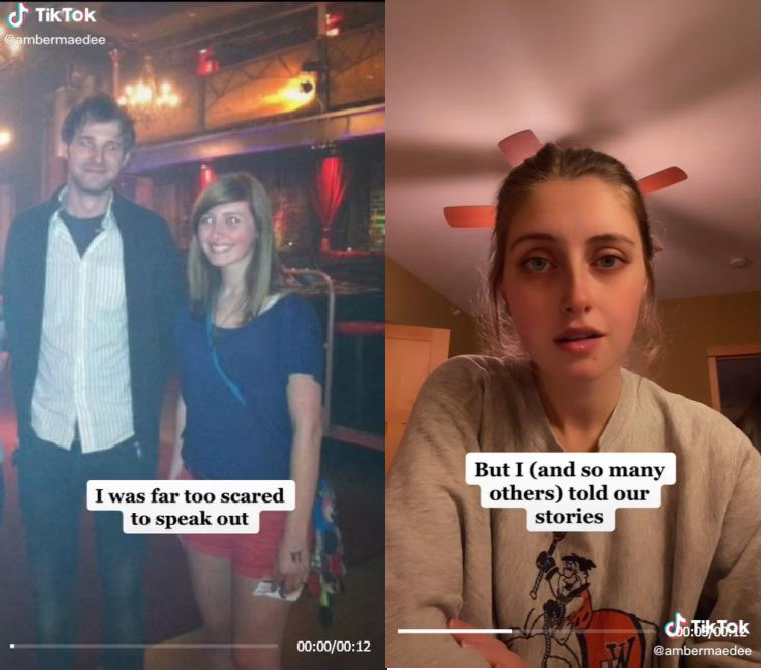

Creators usually follow-up a post with a video, uncovering the story and sharing useful resources to seek help. Like Amber Maedee (@ambermaedee), whose video reached seven million views and 668,000 likes. She shared a photo of herself and former Owl City band member Daniel Jorgensen, with the caption: ‘I was far too scared to speak out, but I (and so many others) told our stories, that’s the thing with assaulting children and abusing fans, the survivors find each other and stick together’.

Generally, the video had an overwhelmingly positive response, with people being empathetic towards her traumatic experience. ‘It is wonderful reading the comments and realising that you’re not alone after all’, Jade explained. ‘Processing trauma becomes easier when you feel like you have a strong support system at your disposal at all times.’

Maedee shared the disturbing story of her 17-year-old self, who ended up being sexually assaulted by Jorgensen, who was 28 at the time. What started as Facebook conversations and meet-ups at shows quickly turned to sexual manipulation: ‘I did not feel safe enough to say no.’ She argued that the reason she has come forward was not only to raise awareness of the whole situation but also to make her audience understand that this is a common occurrence, especially among musicians who take advantage of foolish adolescents.

‘I just wanted to say thank you to everybody who has been so kind and supportive. It does not go unnoticed and it is the reason that people like me can come out about their stories and feel safe’, she said of the people who eventually formed a survivor community in the comment section. ‘Thank you for telling your story. As a victim myself who, to this day, has never felt safe coming forward, this gives me hope’ said user @laceythemosspiglet.

Fender decided to share his appreciation with the people who essentially made him famous by posting a short video in which he thanked those who took part in the challenge for sharing their stories. The artist explained that he feels honoured that his hit song resonated with people in that way, and that he found some of the stories to be ‘really powerful and very honest and brave’. He didn’t hesitate on checking in with his audience one last time: ‘It’s a very special moment for me as a songwriter, so thank you so much and all the love in the world and I hope you’re all OK.’

Legal implications of trial by social media

As for victims publicly exposing their abusers, there might be some serious implications. When asked why she didn’t take part in any TikTok trends before seeking professional help, Jade admitted she was not sure just how much she should share. ‘While I endorse survivors rebelling against victim-blaming by breaking their silence on social media, I think disclosing such sensitive information could potentially affect forthcoming legal proceedings’, said Jade.

Nehal Misra, a student at Nirma University, explains the recurring habit of trial by social media as the tendency of individuals to ‘do a separate investigation and form a public opinion against the accused even before the court takes cognizance of the case’.

Professor Lumby argues that ‘there’s a peril in people just randomly naming perpetrators of sexual assault’. She even goes as far as saying that ‘we don’t want to see trial by social media, we have a criminal justice system.’

What experts are trying to explain to TikTok users is that it is important to draw a clear line between confession and accusation. Essentially, the main aim is that of ensuring that the defendant has the right to a fair trial, without the interference of any external information that might lead the jury or the public to form a biased opinion.

When having unlimited access to such a forceful means of shaping public opinion, even as much as taking part in a TikTok trend and sharing a name can shift the outcome of a trial. ‘The strong sense of community pushes people to deviate by extremes’, Jade explains. ‘I find that supporting the victim on TikTok oftentimes turns into users overly-exaggerating the abusers’ actions, as a means to further pinpoint who’s at fault. But when bringing the matter to court, everything that’s brought in the public domain ends up being discussed and the victim risks jeopardizing their ruling.’

To this day, sexual assault trials in a court of law seem to be doing more bad than good for the victims. ‘I was afraid to relieve the trauma all over again’, Jade confessed. ‘I remember reading about Frances Andrade’s crushing experience in the news, and I felt terrified.’

It comes as no surprise that victims avoid sitting in a witness chair, only to be put through aggressive questioning and be left with a sense of guilt rather than empowerment. Andrade’s case is one of many which serve as proof that cross-examination puts survivors in difficulty by repeatedly accusing them of lying, instead of focusing on bringing them justice.

At the end of the day, thanks to its emphatic audience, TikTok will thrive among social media platforms as the confession booth of the internet — a safe space where empowerment and reassurance are of the greatest importance.

The nature of hearing and being heard on TikTok encourages survivors to share their experiences and gain back power over their abusers. ‘After all is said and done, the community of assault survivors helps speed up the process of healing more than going through the trouble of seeking justice in court would’, said Jade. ‘For those who cannot afford to pay for therapy or cross-examination in court, turning to social media, especially TikTok is regarded as the last resort.’

If you’ve been sexually assaulted or know someone who has, some services can help, such as the 24-hour freephone National Domestic AbuseHelpline, run by Refuge, on 08082000 247 or the Rape Crisis national freephone helpline on 0808802 9999. It is important to keep in mind it is never too late to get help.