The Mandela effect exposes the cracks in our memory – and our media

What is The Mandela Effect and how, with the help of AI, can existing media be changed and tampered with in a way that skewers the truth?

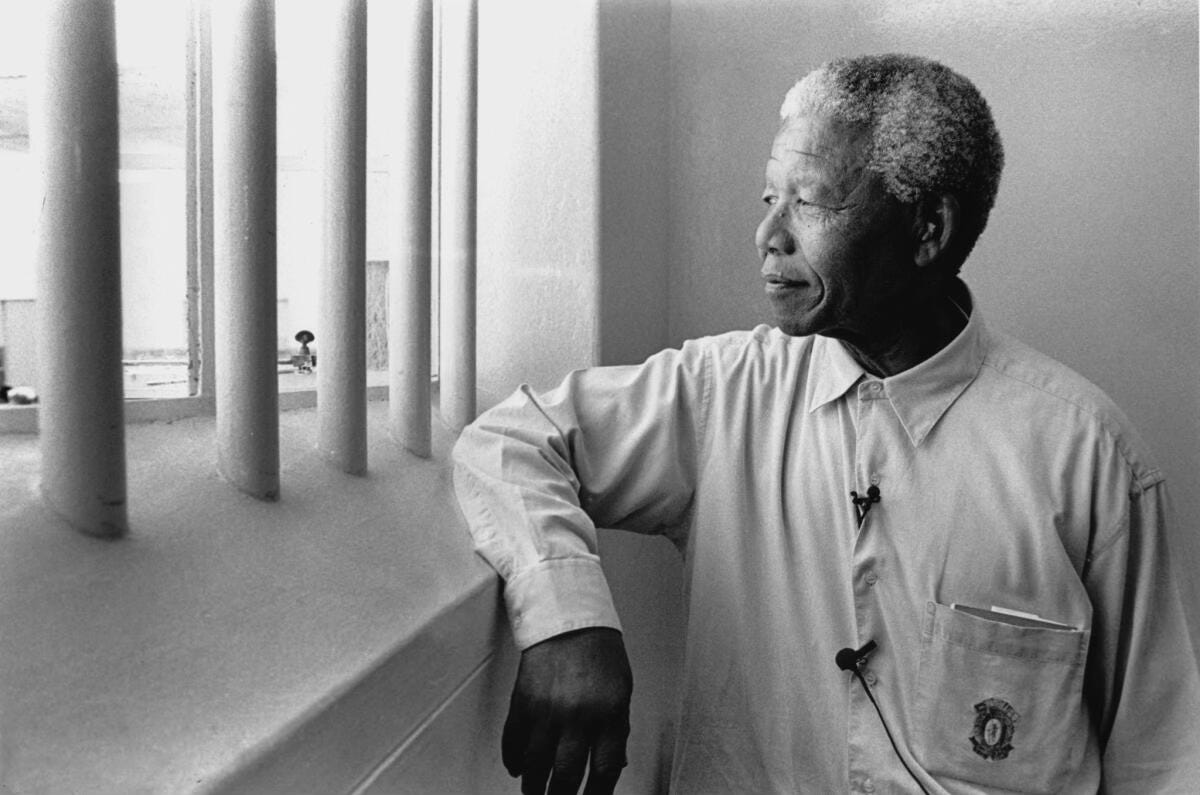

Fiona Broome, paranormal researcher and author, conceptualised The Mandela Effect in 2009 when she discovered that she wasn't alone in her vivid, yet false, memory of the death of South-African anti-apartheid activist and president, Nelson Mandela, while imprisoned during the 1980s. This effect could be described as a strange psychological phenomenon where a large mass of people collectively misremember the same incorrect details, and can happen with historical events, politics or even film quotes.

The Mandela Effect reveals the immense influence of media in shaping public perception, and the rapid spread of confusion and misinformation that these memory quirks can cause is further worsened by the internet. Dr. Olga Barrera, the network chair for the Artificial Intelligence and Data Analytic Network (AIDAN) at Oxford Brookes University, warns in an interview how Artificial Intelligence can increase the severity of the situation, especially through the use of deepfakes, which Barrera describes as “technology that allows people to manipulate audio, videos, images.”

Just as our memory can be altered, so can the digital artifacts we rely on to tell us the truth. AI-generated images, deepfake videos and manipulated audio recordings have blurred the lines between reality and fiction. Dr. Barrera states, “we know that AI can alter anything, essentially, not only history.” In the interview she explains the dangers of misinformation spread through AI, expressing that “with AI in the picture, our understanding of the past could become even more fluid, leading to confusion and doubts about what truly happened. So it's a danger, because you could actually erode or modify a collective memory, and, you know, challenge what we know is true.” She demonstrates how “you could have someone speaking and it's not real, it's a fake, but it looked like the real person in a certain time in history.” proving how easily misinformation could be spread and believed by those who come across it.

The Mandela Effect has served as a warning for the fragility of truth in modern media. At least a simple fault of our memory can be corrected by returning to the source in order to witness the truth, however with the increasing rate of AI and the creation of deepfakes, details can be physically changed to look real by those skilled in this technology. For journalists, this raises pressing ethical concerns for how publications ensure the integrity of factual reporting when AI can fabricate evidence.

In the face of these challenges, critical thinking and media literacy are more important than ever. The Mandela Effect is more than a psychological curiosity; it’s a reminder of how easily reality can be rewritten, whether it is by our minds or by external forces. As Artificial Intelligence continues to evolve, it is crucial to foster scepticism, effective fact-checking and to advocate for transparency in media, otherwise we risk living in a world where reality is uncertain.

“In reality, I think there are lots of steps that have to be made, especially in regulations,” says Dr. Barrera. “We need to intervene in areas such as misinformation, fraud [...] so transparency and disclosure regulation can help become the industry standard in AI ethics.” She proposes that AI developers should be required to implement safeguards to detect manipulated content, alongside public awareness campaigns to improve media literacy and refine skills for detecting AI-generated content.

AI image misinformation has surged in the past couple of years, with a recent NBC News report highlighting the scale of the problem. This report cited new research analysing nearly 136,000 fact-checked claims dating back to 1995. The study, which tracked misinformation trends, revealing that AI accounted for very little image-based misinformation until spring of 2023, right around the time of the viral spread of fake photos of Pope Francis in a puffer coat, a moment that could be viewed as a turning point.

Due to AI’s rapid advancement, the ethical frameworks meant to regulate it are struggling to keep pace. “AI is a tool to help humans to maybe do things faster and release some time to be creative and do new things,” says Dr. Barrera. “So if you see like this, you know, as AI assisting human decision making, rather than replacing humans, that's something that is good, but it needs to be moderated. I think AI tools are developing much faster than any ethical kind of world is.” The problem is that AI tools are developing much faster than ethical oversight can keep up with. We’re seeing this explosion of new technology, but we are still unsure whether it is positive or not. “I think we need to strike a balance.” adds Dr. Barerra. “People working with AI, generative AI or machine learning for different things in different fields, see what are the problems, what can be looked at in a more interdisciplinary way. So that's why the research networks are there.”

With AI-driven misinformation on the rise, the distortion of truth is no longer just a psychological curiosity, but an evolving threat to history, journalism and public trust. When fake images, fabricated audio and manipulated video become indistinguishable from reality, what happens to our ability to discern fact fromm fiction? Dr. Barrera and other experts warn that without urgent regulation, transparency measures and public awareness, we risk entering a world where reality itself is malleable, reshaped by, not by human misremembering, but by technology designed to deceive. The question is no longer whether AI will challenge our perception of the truth, it is now how much control we have left over what we choose to believe.