Your drink looks the same. It tastes the same. But something is wrong

For most, a night out is meant to be fun and carefree, but for some, it turns into a nightmare of fear and shattered trust.

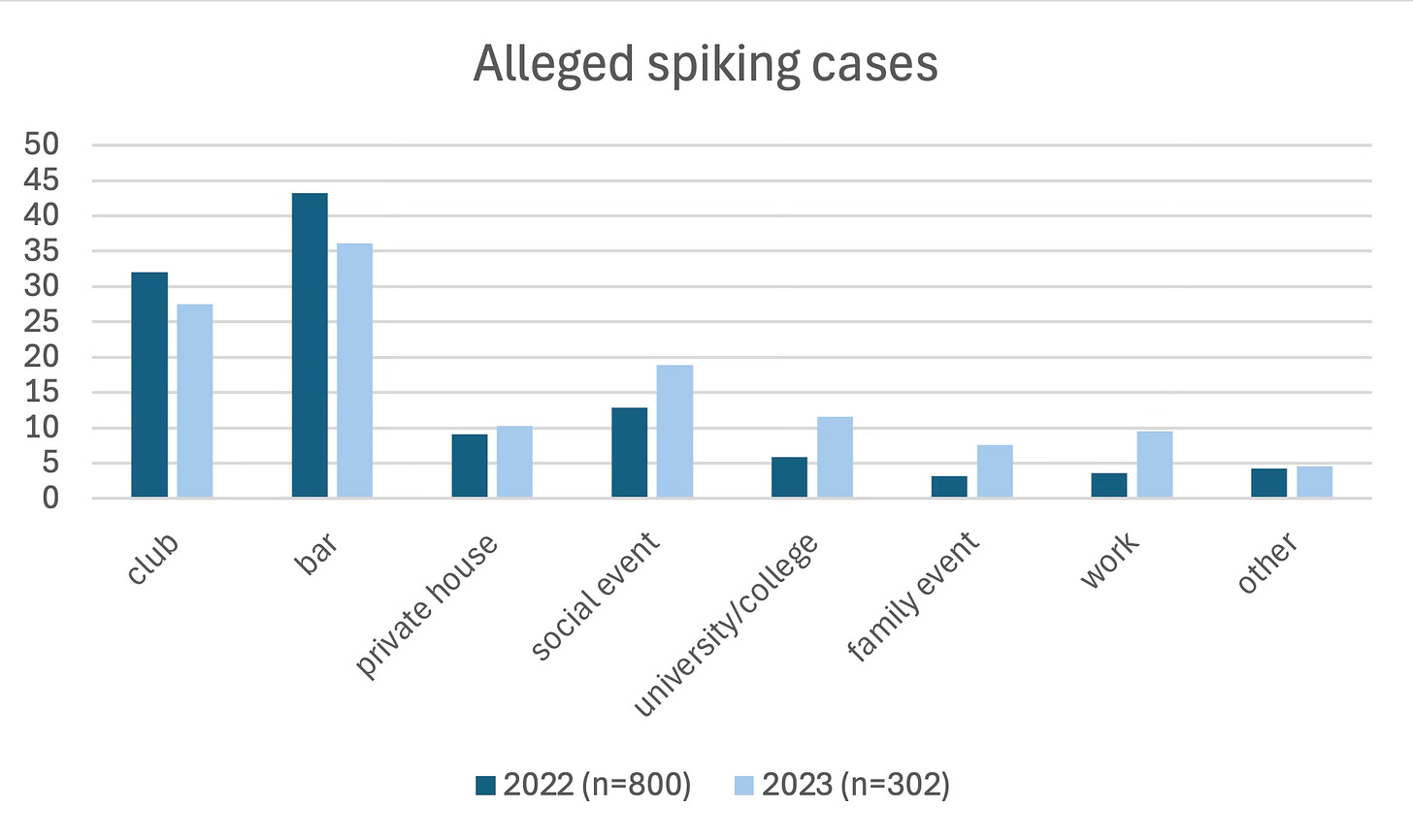

Spiking is the act of adding alcohol or drugs to someone else's drink or injecting them with a needle with the intent to intoxicate them, and it is on the rise in the UK. It's an issue that too often goes unnoticed until it's too late. In a study conducted by Drinkaware, an independent UK-based charity that aims to reduce alcohol-related harm by raising awareness, the largest proportion of drink spiking incidents occured in bars, with clubs being the second largest. The sense of safety and fun that should come with enjoying a drink out on the town is shattered for too many people, leaving them vulnerable, frightened, and often unsure of what has happened to them.

But how are we tackling this epidemic? As of November, the government reiterated promises of a separate law for spiking. Before, there was no single offence for spiking but instead a range of more general offences. The introduction of a specific offence would have benefits that include giving victims confidence that the justice system will support them as well as enabling better data collection by police, which will lead to better reporting on the increasing offences. On top of this, piloted from December, the training to help equip thousands of bar staff with the skills needed to prevent incidents, support victims and help police collect evidence will be rolled out across the country by spring next year.

Despite bars and clubs still being the highest areas of risk, there is a noticeable decline in 2023 compared to 2022 in Drinkawares data for spiking in both, which could be due awareness raised about these instances calling for preventative action to be taken. Unfortunately, in every other instance listed in the study, the more unknown settings of risk such as private homes, social events, family gatherings and work, there is an increase after 2022. This new law could bring more awareness to the scale and possible areas of risk many people may not have known about before and could lead to forestall the number of offenses committed. However, while these new measures offer hope, the issue doesn't just lie in the fact that spiking is happening at a concerning rate, but also in how victims are supported afterwards. According to Drinkaware, almost 90% of victims haven't reported instances of spiking and around half of those said it’s because they ‘don’t see the point.’ Many victims of drink spiking face barriers when seeking help. One victim shared:

“From my experience, I knew something was wrong. A friend, who was also experiencing similar symptoms of spiking, had been separated from me earlier in the night. I later found her with a broken finger and a possible concussion with no idea of how it could have happened. We went to the hospital primarily for her injuries, though while there we also mentioned the possibility of being spiked to a doctor. By the time my friend was finally seen, it was nearing 8 a.m., and we had been left alone in a waiting room for hours. We were exhausted and eager to get home, so we decided not to stay any later to pursue tests for spiking and instead left to sleep it off.”

This story highlights the recurring issue that victims often face hurdles that make it easier to go home than seek answers. Without timely and empathetic support, many incidents remain unreported. Hopefully with these promises of a new law we can reduce the risk of spiking through impeding the effort to commit these offenses and making victims feel safer in coming forward and reporting instiances. Spiking is not just an act of harm– it is a violation of safety and trust.