According to ONS data, the average age for a first-time mother in the UK is 31.

I’m 28, and I assumed I’d have had my first by now.

When I was younger, the ages 25 to 30 sounded like a woman with her life together: crisp shirts, big decisions, skin care with retinol, now I’m here, it’s far from that.

But I’m starting to hear it - the clock. A soft, insistent thrum that makes me peer over the edge into the chaotic, sticky ball pit of motherhood, wondering if I should dive in. I can't right now, but can you blame me for thinking about it?

My ‘For You’ page is a carousel of women cradling screaming infants, somehow managing to keep their homes and wardrobes in perfect, neutral-toned harmony. And when it already feels impossible just to have a baby, doing it in an effortlessly chic way, with a pram that matches your aesthetic? Ridiculous. Everywhere I look - babies. Constant questions from relatives about when and how, not to mention budgeting for it all.

As I approach thirty, I wanted to understand when people are having babies in cold, statistical detail. The truth is, we’re having children later, and more of us are deciding not to have children.

Since 2012, live births in the UK have dropped, falling from 729,674 to 605,479 in 2022 - over 124,000 fewer babies in a single decade. Between 2012 and 2020, the birth rate dropped by 16%. There was a slight uptick in 2021 (pandemic optimism, perhaps? A touch of lockdown boredom?), but 2022 quickly dashed any hopes of a rebound, with a further decline of 3.1%.

The fertility rate (the average number of children a woman would have over her lifetime) has now dropped to just 1.44, the lowest since records began in 1938.

For context: 2.1 is considered the replacement level. We're nowhere near that.

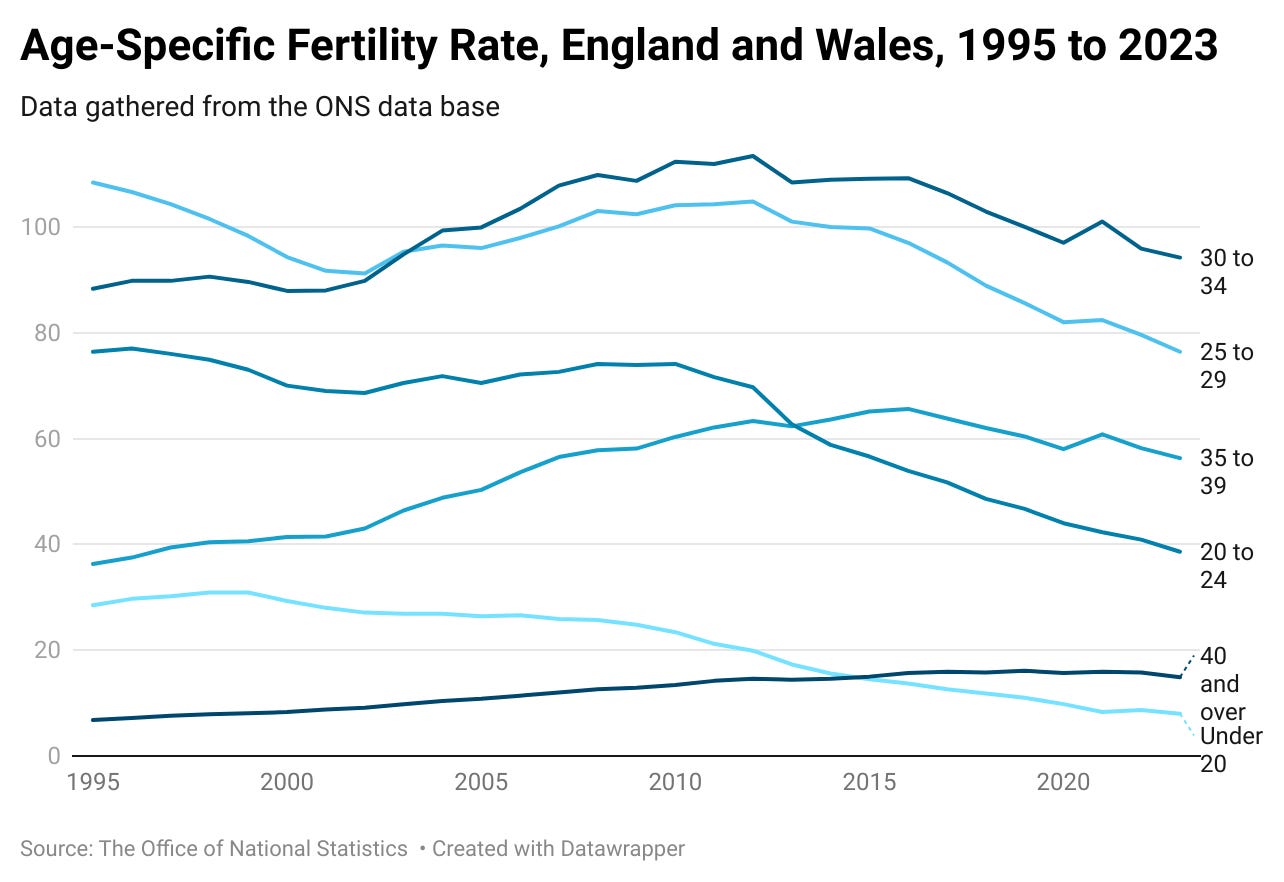

In 1997 - the year I was born - the most common age group for births was 25–29, with over 104 babies per 1,000 women in that range. By 2022, that’s dropped to just 79.6.

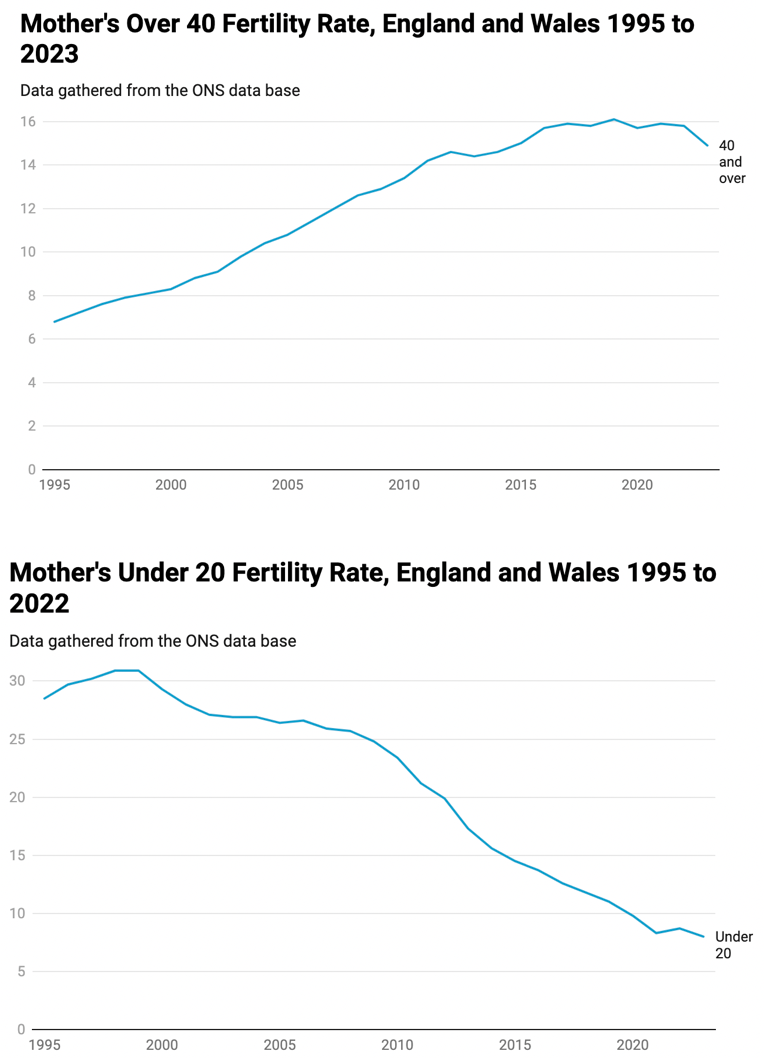

Meanwhile, the rate for women aged 30–34 (now the most fertile group) hovered at 95.9 — steady but slipping slightly. From 1995 to 2022, the number of mothers under 20 has been steadily declining, and those over 40? The rates have more than doubled since the ‘90s.

More women in higher education and the workforce, later marriages, precarious housing markets, mounting childcare costs, and a general feeling that we need to have our lives sorted before adding another one to the mix are some of the many factors at play here.

But the traditional timeline feels almost irrelevant.

There’s something we’re forgetting altogether here. What if you don’t do the baby thing?

Not because you can’t, or didn’t get around to it, or haven’t met the right person, but simply because you don’t want to?

Speaking with Nicola Jones, a philosophy teacher from Oxfordshire, you get a sense of calm clarity; she decided in her twenties not to have children.

“Honestly, I don’t doubt it,” she tells me. “If I did, I’d find a way — I have a friend who had a child on her own, so I know it’s possible. But I simply don’t have that desire.”

Nic’s life is one built around independence and intention. “I value my freedom and the lack of financial pressure that can come with raising children. I make all my own decisions, and I really treasure that.”

Still, she’s no stranger to questions about this -

“‘Oh, you’ll change your mind when you meet the right person.’ I hear it all the time,” she says, “and I resent the idea that I can’t have a firm, independent opinion of my own.”

Her conviction is clear: “If you don’t want to have a baby, don’t. It’s not a failure, not a phase, not something you’ll necessarily regret. It’s a decision.”

Nic has also found strength in community “In the past few years, I’ve made a group of child-free friends, which made me feel less like I had to change who I was to stay socially connected. It reassures me that I’m not unusual — and that this is becoming more normalised.”

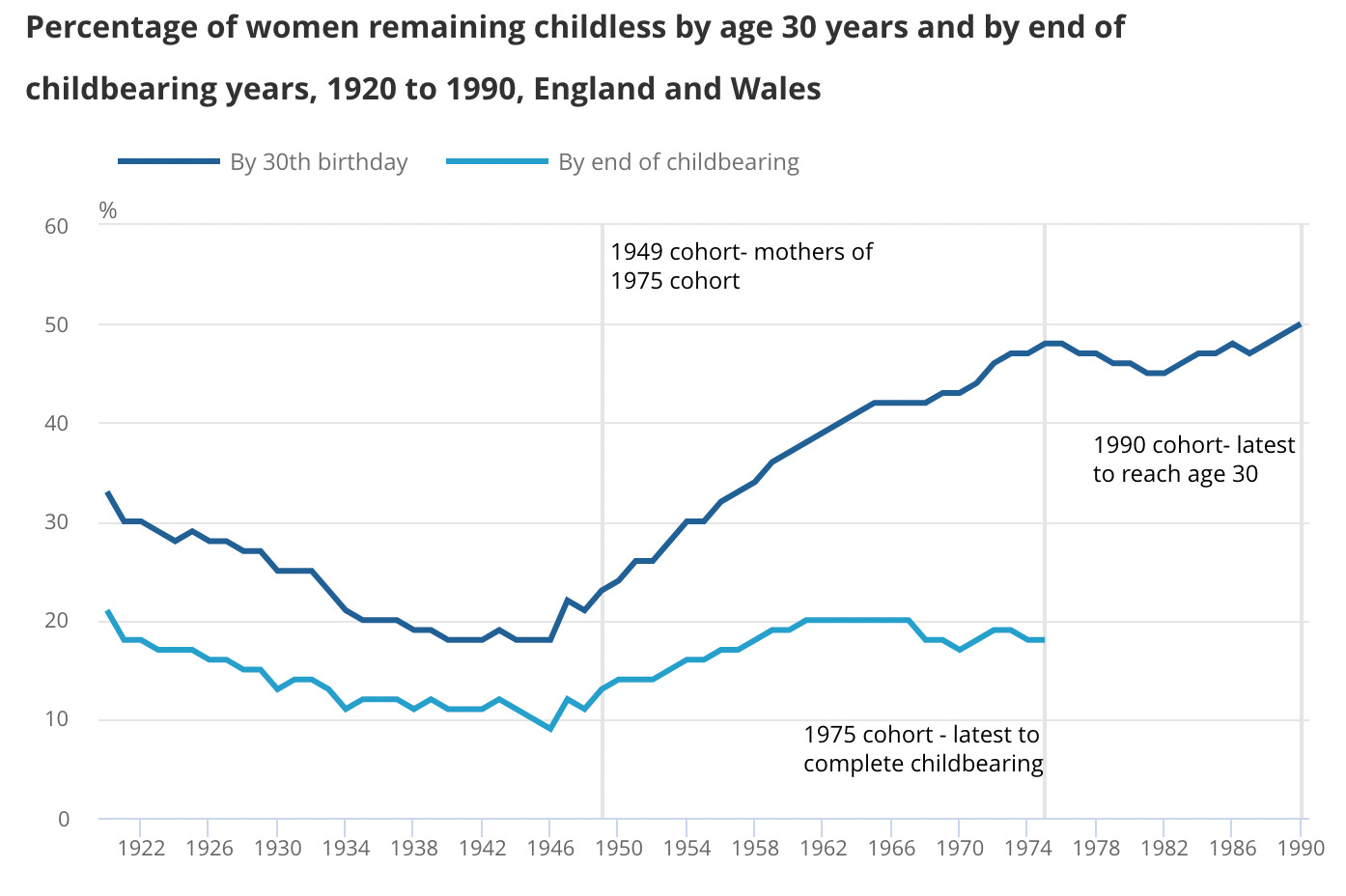

The story of motherhood (or choosing not to) remains deeply political and intensely personal. By 2020, half of the women born in 1990 had reached their 30th birthday without having children — an 18% increase from those born in 1941 and more women like Nic are deciding they simply don’t want to.

But what if you do want children, just not for a while?

I’m hoping to have my first child by my mid-30s. But the longer you wait, the more something else creeps in: judgment, doubt, and a quiet undercurrent of fear.

They call it a “geriatric pregnancy” — a term that sounds less like a medical category and more like an insult. Have a baby at 35, and suddenly, the language around you changes.

Words like possibility, excitement, and joy are replaced with risk, decline, and diminished reserves.

It feels like you can’t win; you’re either too young to be taken seriously or too old to be encouraged. I’ve always known I wanted children. The thing I find myself looping around isn’t the “if” — it’s the when, and I can’t seem to stop the spiral.

So, I did what I always do at times I feel unsure. I asked my mum.

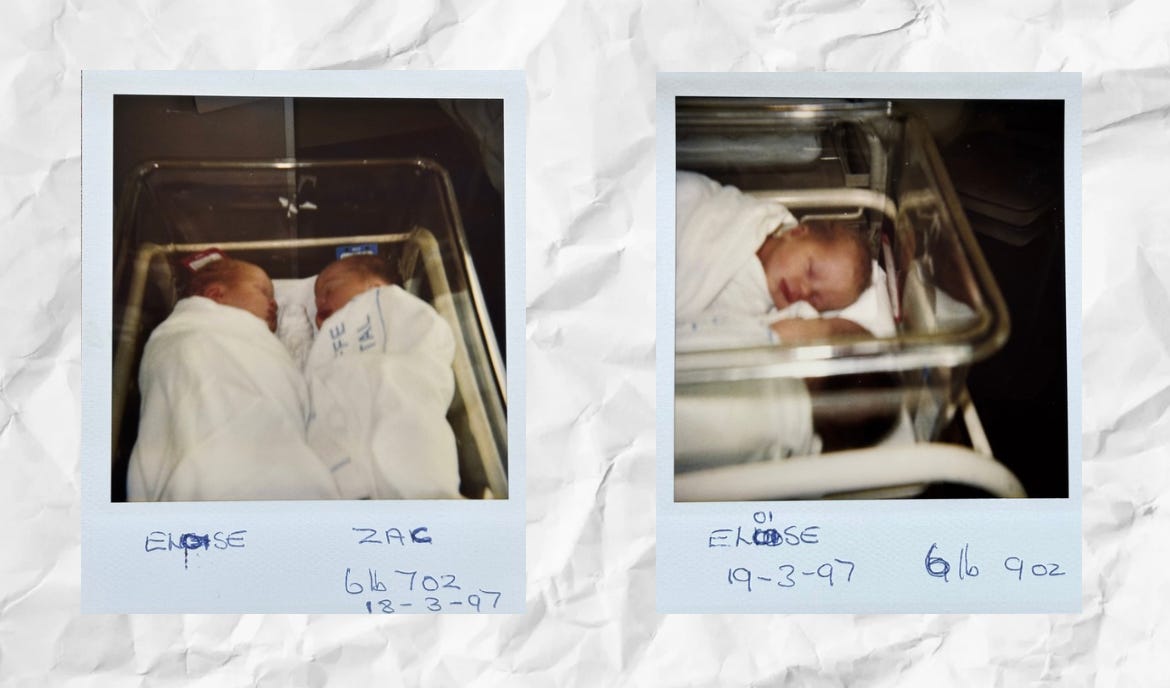

Although she says her pregnancy was well-timed for her, it didn’t come without surprises.

“The most unexpected thing was going to the 20-week scan to be told that there were two!” she recalls, laughing at the memory of finding out my brother and I were twins.

At the start, the journey wasn’t easy. “It was suggested, given my age - 29 - that it would be harder than we thought to conceive,” she says.

When she first found out she was pregnant, things didn’t seem to get much easier. “I felt totally shamed as I went to doctors, having found I was pregnant early on and was told to go away and come back once I got to the twelve-week mark, as most pregnancies don’t make it that far. I was sent away without the ‘blue’ folder and had to wait until I hit 12 weeks.”

“Physically, I felt totally worn out; however, in hindsight, this was because there were two. However, as I didn’t know the difference, it was a case of getting on with it.”

For my mum, pregnancy wasn’t just a physical challenge — it was also an isolating experience.

“I was lonely as no one I was close to had been pregnant before, and there wasn’t the information available that there is today, so I never knew what to expect”.

“You were left to your own devices, really,” she says.

As hard as it all was, the biggest piece of advice she has to offer is something that can be so easy to forget:

“Don’t put so much pressure on yourself; love is the most important thing for babies. It doesn’t have to be that everything has to be neat and organised and ready. A baby doesn’t care how old you are, whether you have a flat tummy within two months of giving birth, they are just happy to be loved and to give love.”

There’s no perfect age to have a baby, and you might decide that it isn’t the right path for you. Maybe the true miracle isn’t in the timing — it’s embracing the journey, whatever it looks like.

It’s your timeline.

Whether you're exploring fertility, considering IVF, or choosing not to have children at all, these links offer clear, compassionate guidance, whatever path you’re on.